- Home

- neetha Napew

The Web Page 9

The Web Read online

Page 9

big, big hand!" Rourke held his cup in his teeth a moment and applauded,

then kept moving toward the woman with the unsmiling face.

Slower country music started to play and the crowd started splitting up.

Rourke cut easily through the wave of people now, some of them gravitating

toward the edge of the square, some pairing off and dancing to the music.

The woman with the unsmiling face apparently wasn't with anyone; she

turned and started away. Rourke downed the rest of his Coke and tossed the

cup into a trash can nearby, then called out to her. "Hey—ahh." The woman

turned around.

Rourke stopped, a few feet from her, saying, "I, ahh—"

"Y'all want to dance?" she smiled.

"All right." Rourke nodded, stepping closer to her.

She slung her handbag in the crook of her left arm on its straps. Rourke

took her right hand in his left, his right

arm encircling her wais*- She was about forty, pretty enough, but not a

woman who seemed to try to be pretty at all.

Her face was smiling, but not her eyes.

"Who are you?" She smiled, coming into his arms.

"John—my name's John," he told her.

"You're carrying a gun, John," she whispered, her head close to his chest.

"I read a lot of detective stories. I'm the librarian. I know."

"You oughta read more," he told her softly. "I'm carrying two."

"Ohh—all right, John."

"Hasn't anyone heard about World War III here?" he asked her, smiling as

they danced their way nearer the blue-grass band.

"If anyone else heard you mention the war, John, the same thing would

happen to you that happened to all the rest of them. We'll talk later, at

my place."

"Ohh." Rourke nodded. He wondered who the rest of them had been. As he

held the woman's hand when they danced, he automatically feit her pulse;

it was rapid and strong. . . .

Nehemiah Rozhdestvenskiy stepped down from the aircraft to the sodden

tarmac of the runway surface. "The weather—it is insane," he shouted to

the KGB man with him.

"Yes, Comrade Colonel." THe man nodded, offering an umbrella, but the

rain—chillingly cold—had already soaked him, and Rozhdestvenskiy watched,

almost amused, as a strong gust of wind caught up the umbrella and turned

it inside out.

He shook his head, and ran through the puddles toward the waiting au

tomobile. He read the name on it as he entered. "Suburban." He ran the

name through his head—it was a type of Chevrolet. . . .

The ride had taken longer than Rozhdestvenskiy had anticipated because he

had been unable to use a helicopter. But as the large Chevy wagon

stopped, he felt himself smiling—it had been worth the wait.

There was already a searchlight trained on the massive bombproof

doors—they had been bombproof at least. They were wide apart now, gaping

into darkness beyond.

"Mt. Lincoln," Rozhdestvenskiy murmured. The presidential retreat.

He stepped out and down, into the mud.

"Comrade Colonel," the solicitous officer, who had tried the umbrella,

said as he joined Rozhdestvenskiy in the mud.

"It is all right, Voskavich—do not trouble over the mud. The facility is

secured?"

"Yes, Comrade Colonel—there were no prisoners." The KGB officer smiled.

"I wanted prisoners."

"They were all dead when we arrived, Comrade. A fault in the

air-circulation system. The bodies, were, ahh . . ." The younger man let

the sentence hang.

"Very well—they were all dead, then." Rozhdestvenskiy dismissed the idea.

"We will enter—it is safe to do so then?"

"Yes, Comrade Colonel." He extracted from under his raincoat two gas

masks.

"This is for—"

"The bodies, Comrade Colonel—they have not all been removed as yet and—"

"I understand." Rozhdestvenskiy nodded. He ran his fingers through his

soaking hair as he started toward the entrance, nodding only at salutes—he

was dressed in civilian clothes—and stopping before the steel doors. "You

were able to penetrate these?"

"One of the particle-beam weapons ordered here by the late Colonel

Karamatsov, Comrade. It was brought here for this purpose I presume?"

"Partly. It is sensitive material that we cannot discuss here in the open.

It was efficient," Rozhdestvenskiy said, looking at the doors and feeling

genuinely impressed. The entire central section of both doors looked to

have been vaporized.

He ran his fingers through his hair again, pulled on the gas mask, and

popped the cheeks, blowij^out to seal it; then he started forward with a

hand torch given him by the younger KGB officer. Through the gas mask,

hearing the odd sound of his own voice, he said, "You will lead the way

for me, Voskavich."

"Yes, Comrade Colonel." The younger man was a captain and Rozhdestvenskiy

decided that the man had no intention of remaining one.

"You have done well, Voskavich. Rest assured, your superiors are aware of

your efficiency."

"Thank you, Comrade," the younger man enthused. "Be careful here,

Comrade—a wet spot and you might slip."

Rozhdestvenskiy nodded, staring ahead of them. There was a lagoon; or at

least there appeared to be one in the darkness of the massive cave inside

the mountain.

"We have boats, Comrade Colonel. The Americans used them I believe to

inspect the lagoon and we must use them to cross it. This was a service

entrance and the most direct route to the presidential suite is—"

"I know, Voskavich; I, too, have read these plans until they were

something I dreamed about. We shall take one of the boats—Charon."

Rozhdestvenskiy laughed at his own joke—the boatman to take him across the

river Styx.

But Voskavich was not the boatman; another KGB man, a sergeant, was

running the small outboard. Rozhdestvenskiy climbed aboard from the lagoon

shoreline, reassessing his nomenclature in terms of the American

language. This would not be a lagoon, but rather a lake because of its

progressively greater depth. A man-made lake? he wondered. None of his

readings of intelligence reports dealing with Mt. Lincoln had ever

indicated the origin of the waters there.

There was a small spotlight jury-rigged to (he helm of the large rowboat;

and between that and the flashlights both Rozhdestvenskiy and Voskavich

held, there was ample light to see the even surface of the waters. At its

widest, Rozhdestvenskiy judged the lake to be perhaps three-quarters of a

mile across. He leaned back as best he could; he liked boat rides, despite

wearing the gas mask, despite the lighting. When he someday returned a

hero to the Soviet Union, he had decided, he would get a boat and a house

on the Black Sea. There were many beautiful women there, and somehow

beautiful women seemed especially fond of influential KGB officers.

And influential he would be if he were able to solidify all the

speculations regarding the Eden Project, and thereby eliminate this last

potential U.S. threat. He favored the most popular theory—that the Eden

Project was a doomsday device. The

Americans had always been kind and

careful people so if they had a doomsday device encircling the globe now,

there would be some way of deactivating it in the event it had been

launched by mistake. He would find that way of deactivating it, then be

the hero.

It was simple.

He even knew where to look for the plans for the device. Part of Mt.

Lincoln held a filing room containing duplicates of the most highly

classified war-related documents, for the reference of the president. It

was there that this most classified of documents would be kept— there that

he would find his answer.

Rozhdestvenskiy felt the motorized rowboat bump

against the far shore of the lake. The ride was over. . . .

Rozhdestvenskiy felt like a graverobber, like an unscrupulous archeologist

invading the tomb of a once-great Pharaoh—and perhaps it was a Pharaoh's

tomb, the tomb of the last real president of the United States. He

discounted this Chambers; he had taken the power, but by all reports from

the late quisling Randan Soames, Chambers had taken the power reluctantly.

The power had not been given him as it was to other American

presidents—such a strange custom, Rozhdestvenskiy thought as he shone the

light of the torch across the gaping mouth of a partially decomposed U.S.

Marine. To hold free elections and trust the mass of the people to select

a leader who was accountable to them.

"No wonder they didn't prevail," Rozhdestvenskiy murmured.

Voskavich asked, "Comrade Colonel?"

"The Americans—their absurd ideas of doing things— it accounts handily for

their failure." The thought crossed his mind, though, that Soviet troops

were now retreading to regroup for the fight against American Resistance

on the eastern seaboard. Their failure had not yet been completely

recognized.

Voskavich stepped across the body of the dead Marine, saying, "These men

were trapped here—perhaps locked inside."

"That is not the American way. They were probably happy to have died in

the service of their country. Give the devihhis due, Voskavich."

Rozhdestvenskiy picked his way over the bodies, seeing ahead of him at the

end of a long corridor what he thought was the room.

It recalled the Egyptian tomb analogy to his mind— fhese Marines, priests

of the order, guardians of the Pharaoh, who was their high priest. The

priests of De-

mocracy—an outmoded religion, Rozhdestvenskiy thought. But he did not

smile. Despite himself, he was saddened to see the death masks o[ these

priests, the anguish, the sorrow, the shock. He wondered what loved ones

they had left behind, what dreams they had held dear. They were young, all

of them, these priests.

He stopped before the "temple." There was a combination lock on the vault

like doors, "I shall need experts in this sort of thing—immediately,"

Rozhdestvenskiy ordered.

"Yes, Comrade Colonel," Voskavich answered, starting to leave. The

younger man paused, turning to Rozhdestvenskiy. "Should I leave you here,

Comrade?"

"The dead cannot hurt me," Rozhdestvenskiy told him. Voskavich left then

and Rozhdestvenskiy stood amid the bodies, by the sealed doors, studying

the faces.

In not one of them could he find disillusionment. They had died for

something important—what was it? Rozhdestvenskiy wondered. . . .

A sergeant, a corporal and two lieutenants had labored over the locking

system ofthedoors,formorelhanahalf hour, and now Voskavich turned to him,

saying, "Comrade Colonel—they are ready."

Rozhdestvenskiy only nodded, then touched his black-gloved right hand to

the door handle, twisting it. Pulling it open toward him, he shone his

light inside. He felt like Carter at the discovery of Tutankhamen. No

golden idols were here, but file cabinets, unopened, unlike the ones in

other parts of the complex. There was no pile of charred papers and

microfilm rolls in the center of the floor.

"No tomb robbers have beaten us»" he remarked,

then stepped inside. He walked quickly through thedark-ness, the light of

his torch showing across the yellow indexes on the file drawers.

He found the one he wanted—the ones. There were six file drawers marked

"Project ,-C/RS." He opened the top drawer to pull out the abstract

sheets at the front of the file. He read them, then closed his eyes,

suddenly very tired.

"Voskavich, these drawers are not to be looked in. I will need carts for

removing the contents after they have been boxed. Bring the cartons here

and I will do that personally."

"Yes, Comrade Colonel Rozhdestvenskiy,' Voskavich answered.

"Leave me here—alone." And Rozhdestvenskiy, when the last one of them had

left, switched off his torch and stood in the darkness beside the file

drawers. He knew now what the Eden Project was. The Americans never ceased

to amaze him.

"I wasn't born here. Most of the rest of them were, and their parents were

born here, too, and before that," the woman told him.

"What the hell does that mean, lady?" Rourke asked her, exasperated,

smiling as he spoke through tightly clenched teeth while the men and women

and children of the town who had made up the knot of humanity in the town

square were now breaking up, going home.

"My name's Martha Bogen." She smiled.

"My question wasn't about your name. Don't these people—"

'That's right, Abe." She smiled, saying the last words loudly, a knot of

people coining up to them, stopping. She looked at a pretty older woman at

the center of a group of people roughly in their sixties, Rourke judged.

She said, "Marion—this is my brother, Abe Collins. He finally made it here

to join me!"

"Ohh," the older woman cooed. "Martha, we're so happy for you—to have your

brother with you. Ohh— Abe," she said, extending a hand Rourke took. The

hand was clammy and cold. "It's so wonderful to meet you after all this

time. Martha's younger brother. I hope we'll

see you in church tomorrow."

"Well, I had a hard ride____I'll try though." Rourke

smiled.

"Good! I know you and Martha have so much to talk about." The older woman

smiled again.

Rourke was busy shaking hands with the others, and as they left, he smiled

broadly at Martha Bogen, his right hand clamping on her upper left arm,

the fingers boring tightly into her flesh. "You give me some answers—

now."

"Walk me home, Abe, and I'll try." She smiled, the smile genuine, Rourke

thought.

"I'll get my bike; it's at the corner." He gestured toward it, half-expect

ing that in the instant since he'd last looked for it someone had taken

it. But it was there, untouched. "I suppose you've got a fully operational

gas station, too?"

"Yes. You can fill up tomorrow. You should stay here tonight—at my house.

Everyone will expect it."

"Why?" Rourke rasped.

"I told them you were my brother—of course." She smiled again, taking his

arm and starting with him through the ever-thinning crowd.

&

nbsp; "Why did you tell them that?"

"If they knew you were a stranger, then they'd have to do something." She

smiled, nodding to another old lady as they passed her.

Rourke smiled and nodded, too, then rasped, "Do what?"

"The strangers—most of them didn't want to stay."

"Nobody's going to think I'm your brother. That was so damned

transparent—"

"My brother was coming. He's probably dead out there

like everybody else. God knows how you survived."

"A lot of us survived—not everyone's dead."

"I know that, but it must be terrible out there—a world like that."

"They know Fm not your brother."

"I know they do," Martha Bogen said, "but it won't matter—so long as you

pretend."

Rourke shook his head, looking at her, saying, his voice low,

"Pretend—what the hell is going on here?"

"I can't -explain it well enough for you to understand, Abe—"

"It's John. I told you that."

"John. Walk me home, then just sleep on the couch; it looks like there's

bad weather outside the valley tonight. Then tomorrow with a good meal in

you—not just those terrible hot dogs—well, you can decide what you want to

do."

Rourke stopped beside his bike. "I won't stay—not now," he told her, the

hairs on the back of his neck standing up, telling him something more than

he could imagine was wrong.

"Did you see the police on the way into town—John?"

"So what?" He looked at her.

ffThey let anyone in, but they won't Jet you out. And at night you won't

stand a chance unless you know the valley. I know the valley. Before he

died, my husband used to take me for long walks. He hunted the valley a

lot—white-tailed deer. I know every path there is."

Rourke felt the corners of his mouth downturning. "How long ago did your

husband die?"

"He was a doctor. You have hands like a doctor, John. Good hands. He died

five years ago. There was an influenza outbreak in the valley and he

worked himself

half to death; children, pregnant women—all of them had it. And he caught

Zero City

Zero City Freedom Omnibus

Freedom Omnibus ACrucible of Time

ACrucible of Time Something MYTH Inc

Something MYTH Inc Forbidden Land

Forbidden Land Corridor of Storms

Corridor of Storms The Peytabee Omnibus

The Peytabee Omnibus Beyond the Sea of Ice

Beyond the Sea of Ice The Time Of The Transferance

The Time Of The Transferance EarthBlood

EarthBlood The Lexal Affair

The Lexal Affair The Web

The Web Slave Ship

Slave Ship Eternity Row

Eternity Row Planet Pirates Omnibus

Planet Pirates Omnibus Aztec

Aztec The Awakening

The Awakening Aztec Blood

Aztec Blood The Mystery of Ireta Omnibus

The Mystery of Ireta Omnibus Aztec Autumn

Aztec Autumn The Savage Horde

The Savage Horde Anti - Man

Anti - Man Deep Trek

Deep Trek Starfall

Starfall The Paths Of The Perambulator

The Paths Of The Perambulator Fool's Fate

Fool's Fate Jinian Stareye

Jinian Stareye Endurance

Endurance Spellsinger

Spellsinger Hybrids

Hybrids Beyond Varallan

Beyond Varallan Doona Trilogy Omnibus

Doona Trilogy Omnibus In th Balance

In th Balance Planerbound

Planerbound The Nightmare begins

The Nightmare begins Humans

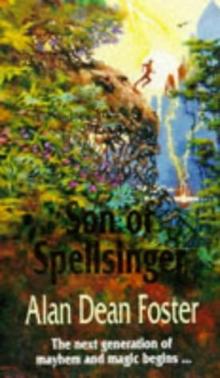

Humans Son Of Spellsinger

Son Of Spellsinger