- Home

- neetha Napew

Jinian Stareye

Jinian Stareye Read online

One

The Great Maze

So far as one could see from the outside, the Great Maze was merely a jungle of paths and hedges, trees and bushes, a mighty entanglement lying to the south of the Pervasion of the Dervishes, stretching from there away to the distant sea. Standing on the hill above the Maze, I had looked down into it to see winding trails, clearings, pathways, even quite large open spaces with impenetrable edges of luxuriant green, and in some of these spaces the easily recognized outline of well-known plants: rainhat bush, thrilps, giant wheat. Only natural things.

I suppose if you took the top of my skull off and looked at the quivering stuff inside, you would see only flesh, only natural things. Looking at that quaking jelly, one wouldn’t see ideas or fears; no dreams would leap from the pinky-gray convolutions to dance on the brain top.

So, when Peter and I stood beside the Great Maze of Lorn - which is the name the Shadowpeople give to this world - we saw no memories rising from the clearings or insinuating their way through the underbrush. And yet, according to Mind Healer Talley, who had told the Dervishes long before, the Maze halds the memories of our world.

Each time I thought of this, my mind chased about for a moment and then stopped working. It was not easy to believe, a whole world, remembering. A world actually thinking, planning. A world dreaming, perhaps. A world regretting. A world dying.

No. Not merely dying. Killing itself.

Outside the Maze were boiling fumaroles casting acid palls onto ageless forests; chasms opening to swallow mighty rivers; mountains bursting into flame and ash. Outside the Maze was a world sick unto death and with no desire for healing. And we were on it, with nowhere else to go.

Oh, yes, part of our fear and pain was for ourselves. Why deny it? And part for those we loved. I fretted, thinking of Murzy and the rest of my seven away south. Peter groaned thinking of Mavin, his mother, and Himaggery the Wizard, his father, and other kin dear to him. And both of us together thought of Queynt and Chance, fondly and with foreboding. At one point I even found myself regretting Queen Vorbold, back in Xammer, for all her unsympathetic pride. But if we went to them, there was nothing we could do to help any of them. If anything could be done, it would be done here, now.

The reason for Lom’s death would be found among those memories.

The reason had to be there, somewhere in the past.

Perhaps if the reason were known, something could be done to reverse this final agony.

There seemed to be no one else to make the attempt.

We might be able to do something. If we were very lucky, it might even be the right thing.

Peter said all this to me, and then I repeated it to him with all the tone and frenzy of conviction. So we encouraged ourselves. Both of us knew that each of us was sick with anxiety and apprehension, and each of us was very busy concealing it from the other. ‘Oh, yes,’ we seemed to say, ‘this is perfectly possible. Of course we will get on with it at once,’ while our stomachs hurt and a smelly sweat oozed on skins already damp. Even I could smell us. A fustigar could have followed us for leagues. We stank of fear, and everything we saw and heard made it clear how late it was to attempt anything at all. If we failed, we died with the world. And even if we succeeded, there was no guarantee we would survive the effort.

I had been inside the Maze once before, only just inside a shallow edge. Cernaby of the Soul had showed me one way in and one way out, and now that Peter and I were going in together, it seemed wise to start by retracing those earlier steps. To get the flavor, so to speak. Or rather, to let Peter get the flavor, since I was afraid I already had it. A flavor of confusion, mostly. Of connections just out of reach. At any rate, after an affectionate and - if we’re honest about it -bravely-hiding-our-true-feelings-for-fear-of frightening-ourselves embrace, we went in hand in hand by the same path I had tried before, an easy path making a short loop into the Maze and out again, the entrance and exit only a few paces apart along the road.

We took one step . . .

... To find ourselves upon a height, sharp with wind. Below lay a cliff-edged bowl carpeted in spring green, sun glinting on the western rim of stone, the depths still in shadow. From above came an enormous screaming, mightier than any fleshy voice, metal on air, burning gasses, hot shrieking wind.

Down from above a silver spearhead, falling butt end first, buoyed on its bellowing, gas-farting rear, down into the green. I smelled the burning; trees burst into flame; the grass crisped into ash; smoke billowed into the morning. Then quiet. A feeling of dread; dread and excitement, curiosity and pain. Mixed.

A door opened high on the silver spearhead, and a strange creature came out. It was too thick through to be normal. Too thin from side to side and too thick from back to front. Not star-shaped, as would have been normal. Limbs oddly jointed. Naked-faced. Not attractive. Ugly, rather. It called with a weak little voice into the shadowed bowl. Um, um, blah, um. Uttering nonsense. Um, um, blah. I knew what it was saying but could not understand a word. A nasty little human creature, an invader, and I could not understand a word.

I shook myself, frightened, grasping Peter’s arm and hanging on as though I were drowning. I had not seen that creature through my own eyes but through the eyes of- the world. Through Lom’s eyes. I gasped, blinked, tried to find myself in all this.

‘Jinian . . . Jinian?’ He was shaking me gently, looking at me with that tender concern he showed sometimes, the kind that made my heart turn over and stop beating.

‘It’s all right,’ I breathed. ‘It’s all right. Let’s get out of here.’ I tugged him to our left along the rim of the cliff, toward the grove of midnight trees. He followed me reluctantly, eyes turned back to watch that silvery vehicle in its patch of burned grass. Just before we reached the tree, the silver vessel disappeared from the green bowl below and we heard the howling begin high above us. As we stepped into the shadow, I looked up. It was coming down again. Below us in the valley the green meadow was untouched; the blackened scar had vanished.

‘What?’ Peter started to say.

‘Shh,’ I said. ‘Just come on a few more steps, then we’ll figure it out.’ I was shaken. When I had been here before, I had merely observed, not been battered about by these waves of feeling.

We stepped out from the shadow of the tree onto the Wastes of Bleer. The place was unmistakable; a high plateau, barren and drear, with the contorted shapes of the Wind’s Bones all around. Thorn bush and devil’s spear and great Wind’s Bones. There was no feeling here, only a waiting numbness.

‘Quick,’ I said to Peter, moving toward the crevasse I remembered from the time before. ‘Before it comes down on our heads.’ Above us, out of a clear sky, a moon was falling at us, burning bright, soundlessly, hideously plunging out of the east. He looked up, gasped, almost fell as I pulled him down into the hole .

Into the great, gray temple I remembered from last time. Outside the walls, the menacing roar of many voices. Above us, a great vacancy, an enormous height. Smoke rising. Somewhere doors opening and closing, the sound far away and vague, as though heard inattentively. Shadowy forms moving around us, back and forth across the immense nave. Two pedestals were toppled against the wall, the lamp that had evidently rested on one of them lay at my feet. Beside the other fallen pedestal was a great book, its leaves crumpled.

Before I could stop him, Peter broke from my side and ran to a carved stone monument that loomed beneath one of the high windows. He was up in it in a moment, neck craned to peer through the opening. I remember being surprised that he Shifted a little as he went, making spidery arms and legs for himself. Somehow I had felt our Talents would not work in the Maze. There was no time to consider it. I cried out, ‘Peter, don’t. ...” afraid he would through into some

other place. He heard the tone of panic in my voice, if not the words, came scurrying back. My heart was pounding; every muscle was tight. I could barely breathe among the feelings of apprehension and horror. We fled around the low curbing of an empty pool toward the stairs and the altar. From high above came the dreadful breaking sound that I remembered half hearing the time before, a sound like a great tree breaking, tearing apart in an agony of ripped fibers. We stepped behind the altar and out onto the path in the Maze. It opened to our right onto the same road we had left.

‘Wah.’ Peter gasped, breathless. ‘Gah. Oh. That wasn’t what I expected.’

I tried to take a deep breath, choking myself in the effort. Horror. Sheer horror. After a time the feeling diminished. I managed to ask, ‘What did you see out the window?’

‘Eesties. I mean, I guess they were Eesties. I’ve never seen them, but Mavin has. And Queynt saw them, of course. I don’t know what else they could have been. Star-shaped. Hundreds, maybe thousands of them, all roaring at the building we were in. Why did you yell at me like that?’

‘I was afraid you’d slip through. Cernaby said each “place” has many ways out. That’s what makes it a maze. If you’d gone somewhere else, I’m not sure I could have found you.’

‘Is it all like that?’

‘I think so. Places. No, not exactly places. More like events. Did you notice that first one we were in? ...”

‘It was the Base. The place the Magicians called the Base. I’ve seen that ship before. I’ve been there.’

‘Have you really!’ Somehow this was astonishing to me. Even though I knew Peter had had a life before we met - or met again - evidence of it always had the power to surprise me, to shame me, as though I felt he could not have survived without me. ‘Then you know what was happening?’

‘It was the human ship arriving. The ship with all the Magicians on it. Barish was on that ship, and Didir, and Queynt himself. It landed a thousand years ago. Didn’t you see Barish come out the door on the side of it? I wanted to get closer and see what Barish was like before - when he was just Barish.’

Barish was no longer just Barish. I knew Peter blamed himself sometimes for putting old Windlow’s mind into Barish’s body, but then at the time we all thought Barish had no mind of his own. Since then, the two of them had lived an uneasy joint tenancy, two sets of memories, two sets of opinions on everything, all in one head, and it would have been interesting to see what Barish was like, just as himself. Nonetheless, we hadn’t time to think of it now.

‘All I could see was something that didn’t look natural,’ I confessed. ‘Even though I knew it was human, I thought it was very strange. I couldn’t understand it.’

‘That’s odd.’ He thought about this, peering at me intently, then nodding. ‘Well, no, not really odd. If these are the memories of the world, as your Dervish friend told you, then you’re probably picking up how the world feels about it. Felt about it. To this world, men would have been strange. Very strange. Come from some far place, not of “itself,” so to speak.’

This made sense. At least it was no stranger than the rest of it, and it would explain the horrifying feelings I had been having.

‘The second place we got into was the Wastes of Bleer,’ mused Peter. ‘At the time the moon fell. You said Storm Grower brought the moon down, just to prove she could. Lorn must have found that traumatic, too.’ He thought for a time longer. ‘And I have no idea what the third place was.’

‘I don’t, either,’ I confessed. ‘But I do know how it’s connected to the other two things.’ It had taken me a while to figure it out, but I had come up with an answer. ‘Just as we came out, there was this sound from above, the sound of something breaking. Like a great beam of wood.’

‘I heard it.’

‘Well, after it broke, I think something fell. Something huge.’

‘So each event was about something falling?’ He sounded doubtful.

‘I think so. Each event was part of a category labeled “Something falling.” Or, more specifically, not merely “something,” but “something very big.” I’m not really sure about that last one, because we didn’t stay to see.’

‘Could we step back in and find out?’

‘I’m afraid to.”

‘Can it hurt us?’

‘Quite frankly, Peter, I haven’t any idea. Reason says no. My skin says yes. I barely made it out of there this time.’

‘You stay here,’ he said, patting me fondly on my head as he might have petted a tame fustigar. He stepped back the way we had come, leaving me with my mouth open. I swallowed, choked, started to go screaming after him, then thought better of it. Peter often did things I was afraid to do. Then my fear for him overcame my fear for myself, and I went roaring after him, usually quite unnecessarily. Just now there was something I had wanted to do that would take a few moments alone. There might be no better time later.

Peter had Shifted inside the maze. If his Talent worked there, then mine would probably work close by. Not my Talent of understanding languages, but my Wize-ardly one. There was a spell I’d been saving, a multiple one Murzy had taught me early on, telling me not to use it save in times of great need. It was a combination spell used to find appropriate destinations. Not particular ones, you understand, but appropriate ones. Murzy called it a blood, dust, and total trust spell. Nothing needed but a drop of my own blood on a roadway and total faith that what I would ask lay in the will and purpose of the art. The problem with it would be, she had said, its tendency to pull other creatures into it with me. Just as the road would be connected to many other roads, so the spell would connect me to many other things. Considering the puzzle the Maze presented, I thought it worth the risk. Our chances of finding what we needed on our own seemed very remote. So, I plopped myself down on the green edge of the path and made myself concentrate. It was hard. Something about the place made concentration difficult, words hard to remember.

‘Day or night, dark or light,’ I prayed, gulping a little, shutting everything out except those words, ‘lead me to the place I need to be. Bright the Sun Burning, Night Will Come Turning, Road’s Dust to Find It, Heart’s Blood to Bind It.’ I used the edge of my star-eye to cut a finger, dropped the blood on a thirsty patch of bare road, then sat very quietly, letting the words flow through me until all my parts understood them.

It always seems to take a long time. Actually, it doesn’t. Within moments, I was worrying about Peter again. There was only time for a modest fret before he emerged from the Maze, somewhat untidily. ‘I Shifted,’ he announced. ‘To stay out of the way. Something enormous fell. It made a noise like some huge being screaming in agony, a great metallic clamor. It killed several whats-its, then after a little while it was gone and everything was just the way it had been originally. It goes on over and over, like some one-act play at a festival. Performances every few minutes.’

‘Did it hurt you?’ I wrapped my punctured finger in a leaf and tucked the star-eye back in my shirt.

‘Oh. No. No, I couldn’t even feel it.’

‘Well, if you can hear it and smell it, how come you can’t feel it?’

‘Probably because the world . . .’

‘Lorn.’

‘Probably because Lom hears it and smells it but doesn’t feel it. I mean, if they’re memories, then they act like memories, don’t you think? If I set myself to remember - oh, that time I tried to rescue you and Silkhands from the Ghoul. Remember that? -I remember the stink, and the heat of the flames, and I can still hear my own voice yelling stupid things, but I don’t burn. I don’t singe. I wince at the memory, but I don’t end up half-asphyxiated from smoke. I remember the fire having happened, but I don’t revoke it, so to speak. The stink, though, that always comes back.’

This, too, made sense. Smell, sight, and hearing happen inside one’s head, but assault comes from the outside world. So the memory of smell could be the smell itself, but the memory of pain . . . Well, creatures probably survive bette

r if they can’t remember pain too well.

He nodded. ‘Of course some memories are very hurtful. It would probably be prudent for us to be careful.’

Now he was talking about prudence. Peter! I didn’t believe it. Agreed with it, yes; believed it, no. Peter had never been prudent in his entire life. He nodded his head a couple of times, as though he were setting that firmly in mind, then asked, ‘Now. Where do we go, and what do we do?’

During the night we’d just spent together, tight-wrapped in each other’s arms and chaste as two baby bunwits, both trying not to say the things that would frighten us to death or make us cry, sometimes he’d dozed off with his lips next to my throat, his breath tickling me like an owl’s feather. It had been necessary then, since I couldn’t sleep, to think of something unemotional, so I’d spent the time thinking about the Maze. Now I trotted out my conclusions, hoping they were correct. ‘If these three events are linked, so to speak, by a single line of thought or category or index heading, then we’ll have to suppose other things are linked in the same way. So. We try to find some line of thought that might logically take us where we want to go.’

‘Which is?’

‘Wherever Lom is thinking about dying.’

He looked depressed. There was nothing I could say to make the task seem either easier or more pleasant. I knew exactly how he felt. It’s how I felt in the Forest of Chimmerdong when something vague and impossible needed doing and I seemed to be the only one around to do it. ‘I know,’ I commiserated. ‘It’s terrible sounding.’

‘It’s not that. You’ve said these events are memories. If Lom is actively thinking about dying, it won’t be in memories, will it? Won’t it be somewhere else? Some other part of its mind?’

I didn’t know. Probably no one did. And if it were so, it was not helpful. ‘They have to be linked together somewhere, Peter.’

He sighed a put-upon sign, not offering any better suggestion. ‘All right. So they must be linked. Now, what shall we look for?’

‘That last place? The temple? There were creatures in it. When the thing fell in, whatever it was, you say something got killed. If I’m right, that means there’s a link out of that place to the idea of things dying. We find that link if we can, and we follow it. Event by event.’

Zero City

Zero City Freedom Omnibus

Freedom Omnibus ACrucible of Time

ACrucible of Time Something MYTH Inc

Something MYTH Inc Forbidden Land

Forbidden Land Corridor of Storms

Corridor of Storms The Peytabee Omnibus

The Peytabee Omnibus Beyond the Sea of Ice

Beyond the Sea of Ice The Time Of The Transferance

The Time Of The Transferance EarthBlood

EarthBlood The Lexal Affair

The Lexal Affair The Web

The Web Slave Ship

Slave Ship Eternity Row

Eternity Row Planet Pirates Omnibus

Planet Pirates Omnibus Aztec

Aztec The Awakening

The Awakening Aztec Blood

Aztec Blood The Mystery of Ireta Omnibus

The Mystery of Ireta Omnibus Aztec Autumn

Aztec Autumn The Savage Horde

The Savage Horde Anti - Man

Anti - Man Deep Trek

Deep Trek Starfall

Starfall The Paths Of The Perambulator

The Paths Of The Perambulator Fool's Fate

Fool's Fate Jinian Stareye

Jinian Stareye Endurance

Endurance Spellsinger

Spellsinger Hybrids

Hybrids Beyond Varallan

Beyond Varallan Doona Trilogy Omnibus

Doona Trilogy Omnibus In th Balance

In th Balance Planerbound

Planerbound The Nightmare begins

The Nightmare begins Humans

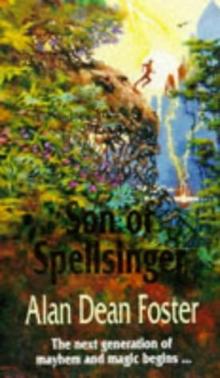

Humans Son Of Spellsinger

Son Of Spellsinger