- Home

- neetha Napew

The Nightmare begins

The Nightmare begins Read online

Chapter One

General Ishmael Varakov buttoned the collar of his greatcoat and pulled the

sealskin chopka down lower on his balding head. "Chicago—another Moscow," he

muttered to himself, shivering, standing in the doorway of his helicopter and

staring across the sea of mud at the icy, wind-tossed Lake Michigan waters

beyond. "Bahh!" he grunted, starting down the rubber-treaded three steps leading

to the damp ground. He stared at the massive edifice less than twenty-five yards

distant. He didn't bother to look for the name—it had been the Museum of Natural

History, given to the city of Chicago for a world's fair decades earlier and

bearing the name of a capitalist, Varakov thought he recalled.

"Put up a new name," he said, turning to his young female aide, watching her

legs a moment as the wind whipped at the hem of her skirt. "You are

freezing—come inside. But the new name I want should reflect that this is

headquarters for the North American Army of Occupation of the Soviet Peoples'

Republic—make a note of this when your hands stop trembling with the wind."

He walked ahead, spurning the blotchy red carpet waiting for him between the

ranks of Kalashnikov-armed, blustery-faced troops, crossing the mud instead, his

mirror-shined jackboots sinking at times several inches into the mire under the

mass of his two hundred eighty-five pounds.

He stopped, standing at the base of the long low steps, scraping the mud from

the soles of his footgear and staring up at the building.

"Comrade General Varakov!"

Varakov turned, staring at the major standing at rigid attention on his left.

Varakov returned the salute, less than formally and grunted, "What is it,

major?"

"General! I have the seventeen partisans ready."

Varakov just stared at the major, then somewhere at the back of his mind he

remembered the radio dispatch given him when he had landed at International

Airport, northwest of the city, before transferring to his helicopter. He could

recall it clearly enough—seventeen armed partisans had been captured after

attacking one of the first Soviet scout patrols sent into the city. The

seventeen—three of them women—had killed twelve Soviet soldiers. The partisans

had survived the neutron radiation when Chicago was bombed, having taken refuge

in an underground shelter. They had been armed with American sporting guns.

"I will come, major," Varakov nodded, then stopped scraping the mud from his

boots—looking in the direction the major pointed, Varakov could see there was

more mud. The major walked beside him, Varakov's young female aide a respectable

distance behind. As Varakov stepped into the mud again, he silently wondered

what it had been like here on the lakefront when the waters had so suddenly

risen. The planetarium less than a quarter mile away had been badly damaged, the

museum—now headquarters— barely touched. The brunt of the force of the Seiche

that had swamped much of the city, destroying everything in its path like a

tidal wave, had hit the northern shoreline. The houses and apartments of the

rich capitalists had been there and were now in ruins. Varakov did not smile at

the thought. The rich, too, had a right to life.

Varakov stared up from the mud, noticing the major had stopped. Looking ahead,

Varakov saw the seventeen—some of them little more than children, none of them

over twenty, he judged. He transferred his stare from the wall where they

stood—hands bound, eyes blindfolded—and looked to the squad of six men,

submachine guns in their gloved hands.

"Would you care to give the order to fire, comrade general?" the major asked.

"No—no, they are your prisoners." Then, stifling his own emotions, he added, "It

is your honor."

The major beamed, executed a salute which Varakov—again less than

formally—returned.

The major executed an about-face and walked to a position beside the firing

squad. "Ready!"

"Aim!"

"Fire!"

Varakov did not turn away as the six-man squad began their steady stream of

automatic fire, the seventeen Americans in front of the wall starting to

crumple. One tried running, his eyes still blindfolded, hands still tied, and

he fell facedown into the mud as two of the soldiers fired at him at once.

Varakov looked again. The one who had tried running had been a young girl, not a

man. As the last body fell, Varakov stared at the wall—it was chipped with

bullet pocks and there were a few dark stains— either from blood or from the mud

that had splashed as the dead people had fallen.

Mechanically—still shivering—Varakov grunted, "Very good, comrade major," this

time not saluting at all.

Chapter Two

Varakov wiggled his toes in his white boot socks under the massive

leather-covered desk at the far end of the central hall. He looked up, for what

must have been, he felt, the hundredth time, at the Egyptian murals on the upper

walls. "Catherine," he grunted, looking across the room at the young aide rising

from her desk and starting across the azure-blue carpet toward him. "Never mind

walking here— order lights. This is too dark here. Go!"

She started a formal about-face and he waved her away, looking back to the

reports littering his desk, Varakov glanced at the Swiss-movement watch on his

left wrist and leaned back into his leather chair. There were ten minutes

remaining before the intelligence meeting. He rubbed the tips of his fingers

heavily across his eyelids and stood up—he hated intelligence meetings because

he resented, distrusted and—secretly—feared and despised the vast power of the

KGB. He recalled the "mysterious" crash of a plane carrying top-level Soviet

naval officers not long before the war had begun—if it had been nothing more

than a crash.

Varakov stood up, looked down to his open uniform blouse and stocking feet and

shrugged his shoulders. As commanding general, he had some advantages, he

reflected. He left the tunic unbuttoned and walked away from his desk. There

were long, low, winding stairs at the rear of the hall leading up to the

mezzanine that overlooked the central hall, and he took these, slowly under his

ponderous overweight, clinging to the rail as he scaled to the top. There were

low benches several feet from the mezzanine rail, and he sat on the nearest of

these and stared down into the hall. A massive, life-size sculpture dominated

the center, of two mastodons fighting to the death. A smile lifted the corner of

Varakov's sagging cheeks. One of the mastodons appeared to be winning the

struggle for supremacy. But to what avail—mastodon as a species was now extinct,

vanished forever from the earth.

Chapter Three

"I've been meaning to ask you," Rubenstein began, wiping his red bandana

handkerchief across his high, sweat-dripping forehead. "Out of all those bikes

back there at t

he crash site, why did you take that particular one?"

Rourke leaned forward on the handlebars of his motorcycle, squinting down at the

road below them, the intense desert sun rising in waves, visible despite the

dark-lensed aviator-framed glasses he wore. "Couple of reasons," Rourke

answered, his voice low. "I like Harley Davidsons, I already have a Low Rider

like this," and, almost affectionately, Rourke patted the fuel tank between his

legs, "back at the survival retreat. It's about the best combination going for

off-road and road use—good enough on gas, fast, handles well, lets you ride

comfortably. I like it, I guess," he concluded.

"You've got reasons for everything, haven't you, John?"

"Yeah," Rourke said, his tone thoughtful, "I usually do. And I've got a very

good reason why we should check out that truck trailer down there—see?" and

Rourke pointed down the sloping hillside and along the road.

"Where?" Rubenstein said, leaning forward on his bike.

"That dark shape on the side of the road; I'll show you when we get there,"

Rourke said quietly, revving the Harley under him and starting off down the

slope, Rubenstein settling himself on the motorcycle he rode and starting after,

as Rourke glanced back over his shoulder at the smaller man.

Perspiration dripped from Rourke's face as well as he hauled the Harley up short

and waited at the base of the slope for Rubenstein. Lower down, the air was even

hotter. He glanced at the fuel gauge on the bike—just a little over half. As he

automatically began calculating approximate mileage, Rubenstein skidded to a

halt beside him. "You've gotta watch those hills, pal," Rourke said, the corners

of his mouth raising in one of his rare smiles.

"Yeah—tell me about it. But I'm gettin' to control it better."

"All right—you are," Rourke said, then cranked his bike into gear and started

across the narrow expanse of ground still separating them from the road. Rourke

halted a moment as they reached the highway, stared down the road toward the

west and started his motorcycle in the direction of his gaze. The sun was just

below its zenith, and as far as Rourke was able to tell they were already into

Texas and perhaps seventy-five miles or less from El Paso. The wind in his face

and hair and across his body from the slipstream of the bike as it cruised along

the highway was hot, but it still had some cooling effect on his skin—already he

could feel his shirt, sticking to his back with sweat, starting to dry. He

glanced into his rearview mirror and could see Paul Rubenstein trying to catch

up.

Rourke smiled.

As he zeroed toward the ever-growing dark spot ahead of them on the highway, his

mind flashed back to the beginning of the curious partnership between himself

and the younger man. Though trained as a physician, Rourke had never practiced.

After several years with the CIA in Latin American Covert Operations, his

interests in weapons and survival skills had qualified him as an "expert"—he

wrote and taught on the subject around the world. Rubenstein had been a junior

editor with a trade magazine publisher in New York City—he was an "expert" on

pipe fittings and punctuation marks. But they had two important things in

common. They had both survived the crash of the rerouted 747 which Rourke had

been taking to Atlanta in order to rejoin his wife and children in northeastern

Georgia. That night of the thermonuclear war with Russia had seemingly gone on

forever. And now Rourke and Rubenstein shared another bond here in the west

Texas desert. Both men had to reach the Atlantic southeast. For Paul Rubenstein,

there was the chance that his aged parents might still be alive, that St.

Petersburg, Florida, had not been a Soviet target and that the violence after

the war had not claimed them. For Rourke—in his mind he could see the three

faces before him—there was the hope that his wife and two children were alive.

The farm where they had lived in northeast Georgia would have survived the bombs

that had fallen on Atlanta. But there were the chances of radiation, food

shortages, murderous brigands— all of these to contend with. Rourke swallowed

hard as he wished again that his wife, Sarah, would have allowed him to teach

her some of the skills that now might enable her to stay alive.

Rourke skidded the Harley into a tight left, realizing he was almost past the

abandoned truck trailer. He took the bike in a tight circle around it as

Rubenstein approached. As he completed the 360 degrees he stopped alongside the

younger man's machine. "Common carrier," Rourke said softly. "Abandoned. After

we run the Geiger counter over it we can check what's inside—might be something

useful. Shut off your bike. I don't think we're gonna find any gas here."

Rourke gave the Geiger counter strapped to the back of his Harley to Rubenstein

and watched as the smaller man carefully checked the truck trailer. The

radiation level proved normal. Rourke walked up to the double doors at the rear

of the trailer and visually inspected the lock.

"You gonna shoot it off?" Rubenstein was asking, suddenly beside him.

Rourke turned and looked at him. "You've gotten awful violent lately, haven't

you? We got a prybar?"

"Nothin' big," the other man said.

"Well," Rourke said, drawing the Metalifed Colt Python from the holster on his

right hip, "then I guess I'm going to shoot it off. Stand over there," and

Rourke gestured back toward the motorcycles. Once Rubenstein was clear, Rourke

took a few steps back, and on angle to the lock, raised the Magn-Na-Ported

six-inch barrel on line with the lock and thumbed back the hammer. He touched

the first finger of his right hand to the trigger, his fist locked on the Colt

Medallion Pachmayr grips, and the .357 Magnum 158-grain semijacketed soft point

round slammed into the lock, visibly shattering the mechanism. Rourke holstered

the revolver. As Rubenstein started for the lock, Rourke cautioned, "It might be

hot," but Rubenstein was already reaching for it, pulling his hand away as his

fingers contacted the metal.

"I said it might be hot," Rourke whispered. "Friction." Rourke walked to the

edge of the shoulder, bent down and picked up a medium-sized rock, then walked

back to the trailer door and knocked the shattered lock off the hasp with the

rock. "Now open it," Rourke said slowly.

Rubenstein fumbled the hasp for a moment, then cleared it and tugged on the

doors. "You've got to work that bar lock," Rourke advised.

Rubenstein started trying to pivot the bar and Rourke stepped beside him.

"Here—watch," and Rourke swung the bar clear, then opened the right-hand door,

reached inside and worked the closure on the left-hand door, then opened it as

well.

"Just boxes," Rubenstein said, staring inside the truck.

"It's what's in them that counts. We could stand to resupply."

"But isn't that stealing, John?"

"A few days ago, before the war, it was stealing. Now it's foraging. There's a

difference," Rourke said quietly, boosting himself onto the rear of the truck

trailer.

"What do you want to forage?" Rubenstein said, throwing

himself onto the truck

then dragging his legs after him.

Rourke, using the Sting IA from its inside-the-pants sheath, cut open the tape

on a small box and said, "Well—what do I want to forage? This might be nice."

Reaching into the box, he extracted a long rectangular box about as thick as a

pack of cigarettes. "Forty-five ACP ammo—it's even my brand and bullet

weight—185-grain JHPs."

"Ammunition?"

"Yeah—jobbers or wholesalers use certain common carriers to ship firearms and

ammunition to dealers. I'd hoped we'd find some of this. Find yourself some 9 mm

Parabellum—may as well stick to solids so you can use it in that MP-40 as well

as the Browning High Power you're carrying. If you come across any guns, let me

know."

Rourke started working his way through the truck, opening each box in turn

unless the label clearly indicated something useless to him. There were no guns,

but he found another consignment of ammunition—.357 Magnum, 125-grain

semijacketed hollow points. He put several boxes aside in case he didn't find

the bullet weight he wanted.

"Hey, John? Why don't we take all of this stuff—all the ammo, I mean?"

Rourke glanced back to Rubenstein. "How are we going to carry it? I can use

.308, .223, .45 ACP and .357—and that's too much. I've got ample supplies of

ammunition back at the retreat once we get there."

"That's still close to fifteen hundred miles, isn't it?" Rubenstein's voice had

suddenly lost all its enthusiasm. Rourke looked at him, saying nothing.

"Hey, John—you want some spare clips—I mean mgazines—for your rifle?"

Rourke looked up. Rubenstein held thirty-round AR-15 magazines in his hands—a

half-dozen. "Are they actual Colt?"

Rubenstein stared at the magazines a moment, Rourke saying, "Look on the

bottom—on the floor-plate."

"Yeah—they are."

"Take 'em along then," Rourke said.

"You sure this isn't dishonest—I mean that we're not stealing?"

Rourke, opening a box of baby food in small glass jars, said, "This is a war,

Paul. A few nights ago, the United States and the Soviet Union had a major

nuclear exchange. The United States apparently didn't fare so well. Every place

we flew over before the 747 crashed looked hit—the whole Mississippi River area

Zero City

Zero City Freedom Omnibus

Freedom Omnibus ACrucible of Time

ACrucible of Time Something MYTH Inc

Something MYTH Inc Forbidden Land

Forbidden Land Corridor of Storms

Corridor of Storms The Peytabee Omnibus

The Peytabee Omnibus Beyond the Sea of Ice

Beyond the Sea of Ice The Time Of The Transferance

The Time Of The Transferance EarthBlood

EarthBlood The Lexal Affair

The Lexal Affair The Web

The Web Slave Ship

Slave Ship Eternity Row

Eternity Row Planet Pirates Omnibus

Planet Pirates Omnibus Aztec

Aztec The Awakening

The Awakening Aztec Blood

Aztec Blood The Mystery of Ireta Omnibus

The Mystery of Ireta Omnibus Aztec Autumn

Aztec Autumn The Savage Horde

The Savage Horde Anti - Man

Anti - Man Deep Trek

Deep Trek Starfall

Starfall The Paths Of The Perambulator

The Paths Of The Perambulator Fool's Fate

Fool's Fate Jinian Stareye

Jinian Stareye Endurance

Endurance Spellsinger

Spellsinger Hybrids

Hybrids Beyond Varallan

Beyond Varallan Doona Trilogy Omnibus

Doona Trilogy Omnibus In th Balance

In th Balance Planerbound

Planerbound The Nightmare begins

The Nightmare begins Humans

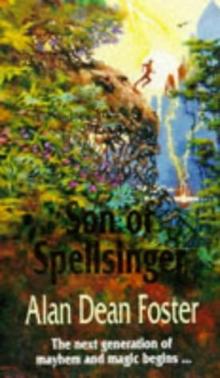

Humans Son Of Spellsinger

Son Of Spellsinger