- Home

- neetha Napew

Forbidden Land Page 6

Forbidden Land Read online

Page 6

A man did not sacrifice sons easily—bravely, but never easily. Torka’s adamant refusal to do the same was an affront to Cheanah, Kimm, their sacrificed twins, and the customs and taboos of their ancestors. It was no wonder that in the continued absence of the magic man, he had called the others together for man talk. Soon he would confront Torka with their concerns.

But Zhoonali had lived long enough to know the hearts of men. The magic man was but a youth, and Torka’s adopted son. His heart was soft with affection for Lonit. If this power of Seeing had allowed him to know that two tiny hearts beat within Lonit, Zhoonali doubted that he would return until the fate of the twins was decided, lest he have to condemn them himself. It would take more than talk to force Torka to abandon his insistence upon keeping his twins alive—but she was not convinced that Cheanah was willing to do more thi that.

Shame was bitter in her mouth. It was an emotion that had been alien to her until Cheanah—with no advice or consent from her—had passively acquiesced to Torka’s leadership. Never before had Zhoonali lived within a band over which one of her men—first grandfather, then father, husband, and sons—had not been headman. She thought it a pity that of all of her sons, Cheanah was the only one who had survived.

True, he had always been the most solicitous. She knew that his love for her was deeper than that of most sons for their mothers. Nevertheless, for all of his bearlike physical attributes and skill as a hunter, there was little aggressiveness in the man. Handsome he was, and more powerful than most, but like a bull musk-ox, his mind was a small, muscle-bound, herd-animal sort. Flexibility and abstract thought were beyond its capacity. It took extensive prodding to rouse anger in Cheanah, and then he became like a riled, rage-maddened bear; only when the herd—his sons, his fat little girl, or his women—were placed in imminent danger of a direct attack could he be provoked into action. He must be provoked now.

Shame became regret as she felt the small life within the crook of her arm flex with a yawn.

For the good of the band and for the sake of my son and my grandsons, this one suckling must not have life lest the forces of Creation bring death to us all as punishment for the arrogance of its parents!

She had promised Torka that she would not interfere with its birth. She had promised that the fate of this child would be determined by the magic man. But for the good of her son, Cheanah, her grandsons, Mano, Yanehva, and Ank, her granddaughter, Honee, and for all of the sons and daughters of the band, this she could not do!

She drew in a deep breath, seeking courage from it, turned on her booted heels, and hurried, unseen, from the encampment. Come, spiritless suckling. This woman must take you far from this camp, to expose your flesh in a place where no man or woman will ever find your bones ... or mine! For when my spirit walks the wind because of a child that should never have been born, my son Cheanah will remember that he is a man who was a headman to his people . a man whose anger will make him headman again. Not even Torka will be able to stand against Cheanah when at last the bear within his grief-stricken spirit is riled.

The wanawut crouched in the shadows. The light from the fissure was still behind it. The magic man’s escape from the cave must be through the fissure, into the light. How was he to get around the beast without losing his life or being dismembered by a single swipe from the wanawut’s great clawed arms? He swallowed, his heart seeming to lodge in his throat. He had heard it said that the spirit of a mutilated body was doomed to haunt the world of men forever, as it searched for its lost parts.

Karana felt light-headed. His choices were clear enough: stay and be consumed, or run for freedom and be killed, horribly injured, or escape through the fissure unscathed. He must focus all his thoughts and energy on getting himself out of this black, foul-smelling cave! He must face the beast wanawut and overcome it, with only a long bone to serve as a weapon.

He tightened his grasp on the bone. Its lightness told him that it had not come from a ‘recent kill. It carried no scent of blood or tissue. The marrow had been sucked from its ends. From its length he judged it to be a leg bone of a camel, bison, horse, or ... of a man? No. That could not be. As far as he knew, with the exception of his own band, there were no people in the Forbidden Land.

He swallowed. The hunters were far away, safe within the winter encampment. He willed his mind to focus on the threat at hand. Karana, son of Navahk, your people call you Magic Man. If they are right.. . if there is any power in you at all, you had best summon it up now!

The beast was circling, making low, quick exhalations that betrayed its nervousness. Was the thing afraid of him? It growled but was not coming any closer. Had it been a man instead of a beast, Karana would have assumed that it was begging for conciliation, for its hideous brow was furrowed as though with concern, and its great arms were gesturing wide, almost in the manner of an old friend beckoning to another who has too long been an enemy.

The magic man found these thoughts preposterous. The beast in the shadows was big and powerful and dangerous, but it lacked one crucial weapon, which made it vulnerable to a man—the ability to reason. Karana, hunching low, circled opposite the wanawut, warning it away with the long bone, jabbing at it with the end from which the ball joint had been chewed to dagger sharpness. The creature stayed back but continued to circle. It stared at the gnawed end of the bone as if it understood the threat. The magic man smiled with relief. The thing could have had him by now, but for reasons that eluded him, it evidently feared him as much as he feared it. If the wanawut kept on circling, the fissure would momentarily be at Karana’s back, and freedom would lie just beyond—if he could get through the opening before the beast made a grab for him.

The moment came. With the long bone in one hand, Karana reached back frantically to loosen stones from where the creature had wedged them into the fissure, to wall up the entrance to its cave. Only a few were small enough to move easily. His fingertips bled as they worked to move the large, cold, rough stones. The beast was coming at him, its eyes wide with anger. Karana screamed in desperation as he swung the long bone at the wanawut. The bone sang as it cut the air and cracked in half against the creature’s forearm. Startled, the wanawut screeched in pain, leaped straight up, and instead of falling upon Karana to make an easy end of his life, cowered back .. . back . -.. into the thinning shadows.

The magic man stood in shock. Beyond the cave, the wind blew ice clouds away from the sun, allowing the full light of day to blossom across the world and stream into the den. Karana could see the wanawut clearly now, and he gasped in horror. The creature was female—hideously, grotesquely female—with long, swollen, milk-encrusted, hairless breasts protruding from her furred chest. She beat her monstrous fists upon her thighs as she made high grunting noises at him.

Behind her, he could see the back of the cave. It was wet, slimed with multicolored algae and moss. Where the ceiling met the bone-and-refuse-littered floor, he could see a nest of spruce boughs and lichens, and in the nest, a cub was stirring, wailing its protest at having been awakened from sleep—a little cub that was not a cub at all but, impossibly, in all ways except for the gray fur that covered it from head to toe, a female human child.

The beast saw his reaction and, sensing danger to her offspring, ran to her nest, swept the cub into her massive, hairy arms, and cradled it against her breasts as she sat cross-legged in her nest. The thing took suck. Karana could not tear his eyes from it. The wanawut was hooting at him as she rocked and rocked, like a demented woman begging for pity. He made himself look away.

And then he saw it: Spread out on a rack of its own bones, a skin was positioned to keep the ceiling moisture from dripping into the nest of the beast—the skin of a man, boned and gutted, arms flung wide, head still attached, one eye open and staring hollowly ... at his son.

Navahk’s eye. Navahk’s skin. The skin of Karana’s father, whose body did not lie buried beneath the collapsed ice walls of the far mountains, after all, but had been brought here to this

cave, to be preserved by the wanawut, the beast that Navahk had seduced into following him across the world like the hideous shadow of his own twisted, malevolent soul. The beast that had borne him a child. A cub. An animal that was Karana’s half sister.

Revulsion and horror were so great in the magic man that he acted without thinking. With a howling shriek of rage, he charged the beast, flailing the broken end of his father’s leg bone. He would kill the cub with it. And in the killing, the wanawut would end his life and his shame.

But the animal rose to deflect his blow and, instead of attacking him, knocked him away gently. He fell. The beast stood over him, mewing softly and touching him with a tenderly reproving hand, as if he were not a man and predator who would kill her and her cub if he could but a long-lost mate.

Suddenly Karana was sick, violently and uncontrollably sick. Men had always said that he looked like his father-like Navahk, the deceiver, the treacherous, slayer of men and raper of women—who had, sometime before the end of his life, mated his power to that of the wanawut to produce an heir that was truly worthy of him. An animal.

The little thing was staring down at him now as its mother held it to her breast. The half-human beast was an affront to the very forces of life, and Karana hurled himself upward at the thing, intending to snap its neck. But the wanawut struck him again, hard this time. He crashed down and slammed the back of his head against a stone and knew no more.

Karana awoke in darkness. The sun was down. The cave was cold. The fissure had been closed by stones. The beast had gone out, taking her child with her.

Slowly, with grim purpose, sensing the hollow eye of his father staring down at him from its lifeless skull, he worked to remove the stones that blocked the den’s entrance. It did not take him long to clear it, and although his fingers were bleeding and sore when he was done, the anguish within his mind was so much greater, he felt no physical discomfort.

Beyond the cave, the new star shone in the night sky, its tail upturned like that of a young colt frolicking across the summer tundra. Karana looked at it somberly. Was it a good omen or bad? He did not know. He did not care. His shame was so great that he did not care whether he lived or died.

Dog sign was everywhere. So Brother Dog had followed him! The ground outside the lair told him that Aar had been at the beast. There was blood on the mountain.

Karana tasted it. It was not Aar’s blood; it was the blood of the beast. He closed his eyes and tried to use his powers to learn whether the creature was alive or dead, but nothing came to him except the small, hairy vision of the cub. He hoped it was dead, along with the monster that suckled it.

It did not take him long to gather up enough dry scrub growth to fire the cave. His fingers were growing stiff, so it was no easy thing to start the fire. He stood and watched the flames draw life from the refuse that littered the floor. The flames threw red and yellow light, the color of the sun. Karana looked through the blaze at what remained of Navahk.

As the flames consumed the skin and skull of his father, he turned away and knew for a certainty that he would never find the magic; it was not meant for the sons of men who coupled with beasts.

In abject misery, he went down from the heights and strode across the hills. He did not know when Brother Dog joined him. They moved across the land together, loping aimlessly beneath the stars while a red aurora slowly washed the night in great, looping rivers that were the color of blood. Karana paid no heed to them. Somewhere along the way the dog cut across his path, forcing him to pause, warning him of dangerous terrain.

To calm the dog he changed his course until, at last, breathless and exhausted, he stopped. Something was conning. He knew it. He felt it. Minutes passed. The earth quivered ever so slightly beneath his feet. He could not have said when the mammoth appeared. Perhaps it had been with him all along, that great, towering mammoth that was Torka’s and his totem. Life Giver .. . Thunder Speaker .. . the great one who had led them from their enemies to safety within the Forbidden Land stood before him, a living mountain, blocking his way.

The dog whined softly. The mammoth was so close that its breath was one with the wind, which stirred the ruined garments of the magic man. Tears rolled down his cheeks.

“I am not worthy of you, Life Giver. Go.”

The mammoth did not go. Instead, it touched the sobbing young man, nudged him with its trunk, urging him on, westward, homeward, as, for the first time since entering the Forbidden Land, the spirit wind—that strange inner turbulence that always preceded Seeing—rose within Karana and made him know that he was a magic man. For the sake of those whom he loved, he knew he must hurry.

The great mammoth was leading, and he would follow, as he had always followed, for in the shadow of his totem, with the Seeing wind rising within his soul, Karana knew that his mystical power was restored.

The first woman of Cheanah stood at the entrance to the hut of blood, holding the door skin back. The sky was afire behind her. “Where is Zhoonali?”

Wallah blinked, taken aback by Xhan’s question. “Gone. A long time gone. To bring the child to its father.”

“Child?”

“Of course! Why do you stare at me like that, Xhan?”

“The burning sky .. . the trembling earth ‘..

Wallah nodded. Fear was growing in her, also. The bad omens had returned, but the head midwife had not. In celebration of the birth of Torka’s second son, the camp should be filled with the sounds of story chanting and revelry. Instead, an unnatural silence filtered through the doorway. Wallah’s mouth puckered over her teeth. “How long must we wait in the hut of blood for Zhoonali to bring us word of the child’s acceptance by its father?”

Xhan frowned. “It has been done. You know that.”

Wallah felt irritable. Something was wrong here. But what?

On her bed of clean furs, which overlay a mattress of freshly laid grasses and lichens, Lonit backhanded sleep from her eyes, sorry that she had drunk so deeply from Wallah’s healing horn; she had slept the entire brief day away without knowing the joy of holding her sons to her breasts. Now it was dark again, and again the sky had caught fire and the earth had trembled. In the eyes of the people of this band, this would bode ill, but Lonit knew that Torka would allow no harm to come to his newborn sons. He had experienced and survived much worse and had come to believe that such phenomena were beyond the influence of men. The lives of men and women mattered little to such great powers as Father Above and Mother Below. Torka was strong in his opinion that signs read from the movement of the earth and sky should be interpreted, acted upon, not propitiated or sacrificed to. Karana, however, disputed this; Lonit was not sure of it; and every band that Torka had ever walked with had condemned him for his arrogance. Now, thinking of her man, she asked to hold her sons and was puzzled when Xhan scowled at her.

“Sons? What are you saying, Woman of the West? The one boy child that Torka unwisely accepted sleeps in the arms of Eneela. Your man continues to stand birth vigil for the second.”

“But the second child was born in the light of yesterday’s dawn,” Lonit said, perplexed. She drew back the furs that covered her. “Look at me, Xhan. I lie on a clean bed. Wallah has taken away the fouled birth grasses and has washed my body. Look. My belly is flat, but my breasts are full and aching to give the milk of life to my sons!”

Wallah, frowning, looked at Xhan. It was quite clear from the expression of Cheanah’s first woman that she had no idea that the second baby had been born. Rising groggily to her feet—Wallah had also drunk deeply of the healing horn and, after days of caring for Lonit, had slept long and deeply—she grunted. Her excess weight, from the prolonged good life in this camp to which Torka had led them, made upward mobility difficult.

Xhan’s eyebrows joined across her narrow, almost bridge less nose. “Zhoonali has not come out from the hut of blood with any second child.”

“But she did!” insisted Wallah. “She didl And told me to wait with Lonit until—�

�� The matron paused for a moment, gathering her thoughts and not liking them at all. “She told me to wait here .. . until she had done .. . what she must do....”

And suddenly, as one, they understood what had happened: The old woman had despaired of the omens. She had taken it upon herself to expose the infant for the good of her people.

Xhan sucked in her breath, and Wallah looked thunderstruck. Lonit stared at them both, and with her hand across her abdomen, she thought of that so very small little life. A single sob of longing escaped her.

“You have a son, Lonit. Be content with that,” consoled Wallah, sweeping across the hut to squat beside the younger woman and take her hand. Her soft eyes brimmed with pity.

Xhan s mouth turned down, and although her eyes were hard, the words that followed were harder. “The old woman has risked her life because Torka and his first woman insisted on granting life to that which should never have been born. Cheanah will be very angry when he learns of this. The band will be angry. I think soon you will have no sons, Woman of the West, for Torka has proved himself unfit to lead. The forces of Creation, with their burning sky and trembling earth, have chosen Cheanah to be headman of this band!”

At Cheanah’s urging, the men of the band followed the trail of the old woman. Although she had done her best to conceal her tracks, she was a female and had not the skills of a hunter.

“Zhoonali has gone far for one of her years,” said Grek, impressed by the physical prowess of the old woman whose walk was leading them eastward into distant hills and difficult terrain.

“Why did she not simply take the thing from camp, pack its mouth and nostrils with moss, and leave it to suffocate while she returned safely to her people?” grumbled old Teean.

“She wanted to be certain that we would not find it.” Simu’s voice was firm and strong with youth, and with resentment as he glanced at Torka. “For the good of the band she wanted to be sure that under no circumstances would it be given life like the other .. . against the wishes of the people.”

Zero City

Zero City Freedom Omnibus

Freedom Omnibus ACrucible of Time

ACrucible of Time Something MYTH Inc

Something MYTH Inc Forbidden Land

Forbidden Land Corridor of Storms

Corridor of Storms The Peytabee Omnibus

The Peytabee Omnibus Beyond the Sea of Ice

Beyond the Sea of Ice The Time Of The Transferance

The Time Of The Transferance EarthBlood

EarthBlood The Lexal Affair

The Lexal Affair The Web

The Web Slave Ship

Slave Ship Eternity Row

Eternity Row Planet Pirates Omnibus

Planet Pirates Omnibus Aztec

Aztec The Awakening

The Awakening Aztec Blood

Aztec Blood The Mystery of Ireta Omnibus

The Mystery of Ireta Omnibus Aztec Autumn

Aztec Autumn The Savage Horde

The Savage Horde Anti - Man

Anti - Man Deep Trek

Deep Trek Starfall

Starfall The Paths Of The Perambulator

The Paths Of The Perambulator Fool's Fate

Fool's Fate Jinian Stareye

Jinian Stareye Endurance

Endurance Spellsinger

Spellsinger Hybrids

Hybrids Beyond Varallan

Beyond Varallan Doona Trilogy Omnibus

Doona Trilogy Omnibus In th Balance

In th Balance Planerbound

Planerbound The Nightmare begins

The Nightmare begins Humans

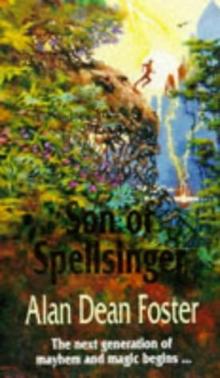

Humans Son Of Spellsinger

Son Of Spellsinger