- Home

- neetha Napew

Aztec Autumn Page 4

Aztec Autumn Read online

Page 4

The entire city was set upon an oval-shaped island, perched in the middle of a sizable lake. That lake's farther edges had no real borders or banks. Its brackish, undrinkable waters simply shallowed away in the distance, all around, merging into oozy swampland that, to the west, merged with the sea. Those swamps exuded dank night mists and pestiferous insects and perhaps evil spirits. My aunt was only one of many people who died every year from a consuming fever, and our physicians asserted that the fever was somehow inflicted on us by the swamps.

Notwithstanding Aztlan's backwardness in many respects, we Aztéca at least ate well. Beyond the marshlands was the Western Sea, and from it our fishermen netted or hooked or gaffed or pried from its bottom not only the common and abundant fishes—rays, swordfish, flatfish, liza, crabs, squid—but also tasty delicacies: oysters, cockles, abalone, turtles and turtle eggs, shrimp and sea crayfish. Sometimes, after much violent and prolonged struggling, usually causing the crippling or drowning of one or more fishermen, they would succeed in landing a yeyemíchi. That is a gigantic gray fish—some can be as big as any palace—and well worth catching. We townsfolk would absolutely gorge ourselves on the innumerable delicious fillets cut from a single one of those immense fish. In that sea, there were also pearl oysters, but we refrained from harvesting them ourselves, for a reason I will tell later.

As for vegetables, besides the numerous edible seaweeds, we had also a variety of swamp-growing greens. And mushrooms could be found sprouting everywhere—frequently even, uninvited, on our houses' ever-damp earthen floors. The only greenery that we actually worked to cultivate was picíetl, dried for smoking. From the meat of coconuts our sweets were confected, and the coconut milk, when fermented, became a drink far more intoxicating than the octli so popular everywhere else in The One World. Another kind of palm tree gave us the coyacapúli fruits, and another palm's inner pulp was dried and ground into a palatable flour. Yet another palm provided us with fiber for weaving into cloth, while shark's skin makes the finest, most durable leather one could want. The pelts of sea otters covered our soft sleeping pallets and made fur cloaks for those who traveled into the high, cold mountains inland. From both coconuts and fish we extracted the oils that lighted our lamps. (I will grant that for any newcomer not inured to the smells of those oils burning, they must have been overpoweringly rank.)

As the Mexíca masters of diverse crafts walked about Aztlan on their first tour of inspection, to see what they might contribute to the city's improvement, they must have had difficulty in containing their laughs or sneers. They surely found our conception of a "palace" ludicrous enough. And our island's one and only temple—dedicated to Coyolxaúqui, the moon goddess, the deity whom in those days we worshiped almost exclusively—was no more elegantly built than was the palace, except for having some conch, whelk, strombus and other shells inset in the plaster around its doorway.

Anyway, the craftsmen were not discouraged by what they saw. They immediately set to work, first finding a place—a comparatively unsoggy hummock some way around the lake from Aztlan—on which to put temporary houses for themselves and their families. Their womenfolk did most of the house building, using what was at hand: reeds and palm leaves and mud daubing. Meanwhile, the men went inland, eastward, having to go no great distance before they were in the mountains. There they felled oak and pine trees, and manhandled the trunks down to flatter riverside land, where they split and burned and adzed them into acáltin, far bigger than any of our fishing craft, big enough to freight ponderous burdens. Those burdens also came from the mountains, for some of the men were experienced quarriers, who searched for and found limestone deposits, and dug deep into them, and broke the stone into great chunks and slabs. Those they roughly squared and evened on the site, then loaded them into the acáltin, which brought them down a river to the sea, thence along the coast to the inlet leading to our lake.

The Mexíca masons smoothed and polished and used the first-brought stone to erect a new palace, as was only proper, for my Uncle Mixtzin. When completed, it might not have rivaled any of the palaces in Tenochtítlan. For our city, though, it was an edifice to marvel at. Two stories high, and with a roof comb making it twice that tall, it contained so many rooms—including an imposing throne room for the Uey-Tecútli—that even Yeyac, Améyatl and I had each a separate sleeping room. That was something almost unheard of then, in Aztlan, for any person, let alone three children aged twelve, nine and five, respectively. Before any of us moved in, however, a swarm of additional workers did—carpenters, sculptors, painters, weaver-women—to decorate every room with statuettes and murals and wall hangings and the like.

Other Mexíca, at the same time, were cleansing and rechanneling the waters in and around Aztlan. They dredged the old muck and garbage from the canals that have always crisscrossed the island, and lined those with stone. They drained the swamps around the lake, by digging new canals that drew off the old water and let in new from streams farther inland. The lake remained brackish, being of commingled fresh water and seawater, but it no longer stood stagnant, and the marshes began to dry into solid land. The result was an immediate diminution of the noxious night mists and the former troublesome multitudes of insects and—proving that our physicians had been right—the swamp spirits thereafter vexed only one or two persons each year with their malign fevers.

In the meantime, the masons went straight from building the palace to building a stone temple for our city's patron goddess, Coyolxaúqui, a temple that put the old one to shame. It was so very well designed and graceful that it made Mixtzin grumble:

"I wish now that I had not trundled to Tenochtítlan the stone depicting the goddess—now that she has a temple befitting her serene beauty and goodness."

"You are being foolish," said my mother. "Had you not done that, we would not now have the temple. Or any of the other benefactions brought by that gift to Motecuzóma."

My uncle grumbled some more—he did not like having his convictions disputed—but had to concede that his sister was right.

Next, the masons erected a tlamanacáli, in a manner that we all thought most ingenious, practical and interesting to watch. While the stoneworkers laid inward-slanting slabs, making a mere shell of a pyramid, ordinary laborers brought tumplined loads of earth, stones, pebbles, driftwood, just about every kind of trash imaginable, and dumped that in to fill the stone shell and tamped it firmly down inside. So eventually there arose a perfect tapered pyramid that seemed to be of solid shining limestone.

It was certainly substantial enough to hold high aloft the two small temples that crowned it—one dedicated to Huitzilopóchtli, the other to the rain god Tlaloc—and to support the stairway that led up the height of its front side, and the innumerable priests, worshipers, dignitaries and sacrificial victims who would tread those stairs in the ensuing years. I do not claim that our tlamanacáli was as awesome as the famous Great Pyramid in Tenochtítlan—because, of course, I never saw that one—but ours was surely the most magnificent structure standing anywhere north of the Mexíca lands.

Next, the masons erected stone temples to other gods and goddesses of the Mexíca—to all of them, I suppose, though some of the lesser deities had to group in threes or fours to share a single temple. Among the many, many Mexíca who had come north with my uncle were priests of all those gods. During the early years, they worked alongside the builders, and worked just as hard. Then, after they all had temples, the priests also devoted time—besides attending to their more spiritual duties—to teaching in our schools, which were the next-constructed buildings. And, after those, the Mexíca turned to the erection of less important structures—a granary and workshops and storehouses and an armory and other such necessities of civilization. And finally they set about bringing lumber from the mountain forests and building stout wooden houses for themselves as well as every Aztéca family that wanted one, which included everybody except a few malcontent and misanthropic hermits who preferred the old ways of life.

&

nbsp; When I say that "the Mexíca" accomplished this or that, you must realize that I do not mean they did it unaided. Every group of quarriers, masons, carpenters, whatever, conscripted a whole team of our own men (and, for light labor, women and even children) to assist in those projects. The Mexíca showed the Aztéca how to do whatever was required, and supervised the doing of it, and continued to teach, chide, correct mistakes, reprove and approve until, after a while, the Aztéca could do a good many new things on their own. I myself, well before my naming-day, was carrying light loads, fetching tools, dispensing food and water to the workers. Women and girls were learning to weave and sew with new materials—cotton, metl cloth and thread, egret feathers—much finer than the palm fibers they had formerly used.

When our men came to the end of each workday, the Mexíca supervisors did not just let them go home to lie around and get drunk on their fermented coconut potation. No, the overseers turned our men over to the Mexíca warriors. Those, too, might already have put in a full day of hard work, but they were indefatigable. They put our men to learning drills and parading and other military basics, then to the use—eventually the mastery—of the maquáhuitl obsidian sword, the bow and arrow, the spear, and then to learning various battlefield tactics and maneuvers. Women and girls were exempted from this training; anyway, not many of them were inclined, as their men had been, to waste their free time in drinking and indolence. Boys, myself included, would have been overjoyed to partake of the military training, but were not allowed until they were of age to wear the loincloth.

Mind you, none of this total remaking of Aztlan and remolding of its people took place all of a sudden, as I may have made it sound. I repeat, I was a mere child when it all began. So the clearing away of the old Aztlan and the raising up of the new seemed—to me—to keep pace with my own growing up, growing stronger, growing in maturity and sapience. Hence, to me, what happened to my hometown was equally imperceptible and unremarkable. It is only now, in retrospect, that I can recall in not too many words all the very many trials and errors and labors and sweats and years that went into the civilizing of Aztlan. And I have not bothered to recount the almost-as-many setbacks, frustrations and failed attempts that were likewise involved in the process. But the endeavors did succeed, as Uncle Mixtzin had commanded, and on my naming-day, just those few years after the coming of the Mexíca, there were already built and waiting the telpochcáltin schools for me to start attending.

In the mornings, I and the other boys my age—plus a goodly number of older boys who had never had any schooling in their childhood—went to The House of Building Strength. There, under the tutelage of a Mexícatl warrior assigned as Master of Athletics, we performed physical exercises, and learned to play the exceedingly complicated ritual ball game called tlachtli, and eventually were taught elementary hand-to-hand combat. However, our swords and arrows and spears bore no obsidian blades or points, but merely tufts of feathers wetted with red dye to simulate blood marks where we struck our opponents.

In the afternoons, I and those same boys—and girls of the same ages—attended The House of Learning Manners. There an assigned teacher-priest taught us hygiene and cleanliness (which quite a few lower-class children knew nothing about), and the singing of ritual songs, and the dancing of ceremonial dances, and the playing of a few musical instruments—the variously sized and tuned drums, the four-holed flute, the warbling jug.

In order to perform all the ceremonies and rituals properly, we had to be able to follow the tunes and beats and movements and gestures exactly as they had been done since olden times. To make sure of that, the priest passed around among us a roughly pictured page of instructions. Thus we came to grasp at least the rudiments of word-knowing. And when the children went home from school, they taught what they had learned of it to their elders—because both Mixtzin and the priests encouraged that passing-along of knowledge, at least to the grown-up males. Females, like slaves, were not expected ever to have any need of word-knowing. My own mother, though of the highest noble rank attainable in Aztlan, never learned to read or write.

Uncle Mixtzin had learned, beginning back when he was just a village tlatocapíli, and he went on learning all his life long. His education in literacy was begun under the instruction of that long-ago Mexícatl visitor, the other Mixtli. Then, during my uncle's return journey from Tenochtítlan, with all those other Mexíca in his train, at every night's camp he would sit down with a teacher-priest for further instruction. And, from their first arrival in Aztlan, he had kept by him that same priest for his private tutoring. So, by the time I started my schooling, he was already able to send word-picture reports to Motecuzóma regarding Aztlan's progress. And more: he even entertained himself by writing poems—the kind of poems that we who knew him would have expected him to write—cynical musings on the imperfectibility of human beings, the world and life in general. He used to read them to us, and I remember one in particular:

Forgive?

Never forgive,

But pretend to forgive.

Say amiably that you forgive.

Convince that you have forgiven.

Thus, devastating is the effect

When at last you lunge

And reach for the throat.

Even in the lower schools, we students were taught a bit of the history of The One World, and young though I was, I could not help noticing that some of the things we were told were considerably at variance with a few tales that my great-grandfather, Aztlan's Rememberer of History, had occasionally confided to our family circle. For example, from what the Mexícatl teacher-priest taught, one might suppose that the whole nation of Mexíca people had simply sprung up one day from the earth of the island of Tenochtítlan, all of them full-grown, in full strength and vigor, fully educated, civilized and cultured. That did not accord with what I and my cousins had heard from old Canaútli, so Yeyac, Améyatl and I went to him and asked for elucidation.

He laughed and said tolerantly, "Ayya, the Mexíca are a boastful people. Some of them do not hesitate to contort any uncomfortable facts to fit their haughty image of themselves."

I said, "When Uncle Mixtzin brought them here, he spoke of them as 'our cousins,' and mentioned some kind of 'long-forgotten family connection.' "

"I imagine," said the Rememberer, "that most of the Mexíca would have preferred not to hear of that connection. But it was one fact that could not be avoided or obscured, not after your—not after that other Mixtli stumbled upon this place and then took the word of our existence back to Motecuzóma. You see, that other Mixtli asked me, as you three have just done, for the true history of the Aztéca and their relation to the Mexíca, and he believed what I told him."

"We will believe you, too," said Yeyac. "Tell us."

"On one condition," he said. "Do not use what you learn from me to correct or contradict your teacher-priest. The Mexíca are nowadays being very good to us. It would be wicked of you children to impugn whatever silly but harmless delusions it pleases them to harbor."

Each of us three said, "I will not. I promise."

"Know then, young Yeyac-Chichiquíli, young Patzcatl-Améyatl, young Téotl-Tenamáxtli. In a time long ago, long sheaves of years ago—but a time known and recounted ever since, from each Rememberer to his successor—Aztlan was not just a small seaside city. It was the capital of a territory stretching well up into the mountains. We lived simply—the folk of today would say we lived primitively—but we fared well enough, and seldom suffered the least hardship. That was thanks to our moon goddess Coyolxaúqui, who saw to it that the dark sea's tides and the mountains' dark fastnesses provided bountifully for us."

Améyatl said, "And you once told us that we Aztéca worshiped no other gods."

"Not even those others as beneficent as Coyolxaúqui. Tlaloc, to name one, the rain god. For look about you, girl." He laughed again. "What need had we to pray that Tlaloc give us water? No, we were quite content with things as they were. That does not mean we were hapless wea

klings. Ayyo, we would fiercely defend our borders when some envious other nation might try to encroach. But otherwise we were a peaceable people. Even when we made sacrificial offerings to Coyolxaúqui, we never chose a maiden to slay, or even a captured enemy. On her altar we offered only small creatures of the sea and of the night. Perhaps a strombus of perfectly shaped and unblemished shell... or one of the big-winged, soft-green moon moths..."

He paused for a bit, apparently contemplating those good old days, long before even his great-grandfather was born. So I gently prompted him:

"Until there came the woman..."

"Yes. A woman, of all things. And a woman of the Yaki, that most savage and vicious of all peoples. One of our hunting parties came upon her, wandering aimlessly, high in our mountains, alone, infinitely far from the Yaki desert lands. And those men fed and clothed her and brought her here to Aztlan. But, ayya ouíya, she was a bitter woman. When our ancestors thus befriended her, she repaid them by turning Aztéca friends against friends, families against families, brothers against brothers."

Yeyac asked, "Had she a name?"

"An ugly-sounding Yaki name, yes, G'nda Ké. And, what she did—she began by deriding our simple ways and our reverence for the kindly goddess Coyolxaúqui. Why, she asked, did we not instead revere the war god, Huitzilopóchtli? He, she said, would lead us to victory in war, to conquer other nations, to take prisoners to sacrifice to the god, who would thus be persuaded to lead us to other conquests, until we ruled all of The One World."

"But why," asked Améyatl, "would she have sought to foment such alien passions and warlike ambitions among our peaceable people? What profit to her?"

"You will not be flattered to hear this, great-granddaughter. Most of the earlier Rememberers simply attributed it to the natural contrariness of all women."

Améyatl only wrinkled her pretty nose at him, so Canaútli grinned toothlessly and went on:

Zero City

Zero City Freedom Omnibus

Freedom Omnibus ACrucible of Time

ACrucible of Time Something MYTH Inc

Something MYTH Inc Forbidden Land

Forbidden Land Corridor of Storms

Corridor of Storms The Peytabee Omnibus

The Peytabee Omnibus Beyond the Sea of Ice

Beyond the Sea of Ice The Time Of The Transferance

The Time Of The Transferance EarthBlood

EarthBlood The Lexal Affair

The Lexal Affair The Web

The Web Slave Ship

Slave Ship Eternity Row

Eternity Row Planet Pirates Omnibus

Planet Pirates Omnibus Aztec

Aztec The Awakening

The Awakening Aztec Blood

Aztec Blood The Mystery of Ireta Omnibus

The Mystery of Ireta Omnibus Aztec Autumn

Aztec Autumn The Savage Horde

The Savage Horde Anti - Man

Anti - Man Deep Trek

Deep Trek Starfall

Starfall The Paths Of The Perambulator

The Paths Of The Perambulator Fool's Fate

Fool's Fate Jinian Stareye

Jinian Stareye Endurance

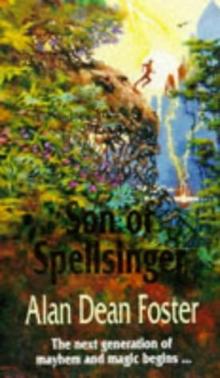

Endurance Spellsinger

Spellsinger Hybrids

Hybrids Beyond Varallan

Beyond Varallan Doona Trilogy Omnibus

Doona Trilogy Omnibus In th Balance

In th Balance Planerbound

Planerbound The Nightmare begins

The Nightmare begins Humans

Humans Son Of Spellsinger

Son Of Spellsinger