- Home

- neetha Napew

Anti - Man Page 4

Anti - Man Read online

Page 4

He didn’t answer.

I sat down next to Him. The snow was falling harder now, though it still might be only a local storm or even a short-term squall. He didn’t speak, and I didn’t feel like interrogating Him. We sat for about five minutes until the warmth we had gained from marching drained out and the cold began seeping back into my bones. He had given way completely to that unknown part of His personality, and I could not see how to approach Him, how to ask what was the matter. When another five minutes passed, I decided on the blunt route. “What is it?” I asked.

“Jacob, I am sitting here in a quandary, faced with two decisions, each of which will be in some way unpleasant.” He spoke in that same, deep, even tone that denied emotion. That was what a machine should sound like - not like a seductress. “One of the courses of action that is open to me will end with your becoming a little less sure of me, a little frightened of me.”

“No,” I said.

“Yes, it will I know. You will be slightly disgusted, and it will have a bearing on the way you feel about me. Maybe small, maybe large. I don’t want to lose your friendship.”

“The second alternative?”

“I can postpone continuation of the changes going on in me, lose the momentum of biological processes, and wait until we are to the cabin to begin. It might mean a lost day.”

“What are you trying to say?” Despite myself, I let a note of fear slip through my words. It must have showed, for He grinned and slapped my back.

“I need food,” He said. “I can’t wait until we get to the cabin. I’ve started new systems, and I would suffer a complete setback if I had to wait much longer for food to create the energy needed to form large quantities of muscle tissue.”

“I don’t see how you propose to get food out here. Also, I don’t see what you could possibly do to upset me.”

“All right,” He said. “I will not postpone the changes. If you do not like what happens, try to remember that it is necessary.”

He took off His gloves again and knelt on the earth. He pressed His fingers against the ground after brushing the snow away over a two-foot square area. As I watched, His hands seemed to melt and run into the soil. The frozen ground cracked and spattered up as His lengthening fingers probed and displaced it. Several minutes later, He smiled and withdrew His hands, His fingers flowing back into normal shape as if they had been rubber that had been stretched and now released. “I found two of them,” He said mysteriously. “Over there.”

“What?” I asked.

“Watch.”

I followed him across the clearing to a jumble of rotting logs and brush. He hefted the logs aside effortlessly, revealing a burrow of some sort. He reached into it, and He made His arm grow longer now, not just His fingers. Abruptly, there was a squealing and thrashing from inside the burrow. He drew His arm back out, a snow rabbit clutched in His fist. The animal had been strangled. A few moments later, He had done the same thing to a second rabbit and had brought it out and placed it next to the first. “This is the part you may find disgusting,” He said. “I’ll have to eat them raw. No time for a fire and too risky to start one anyway.”

“Doesn’t bother me,” I said, though I was not too sure what I felt. The blood wouldn’t bother me, certainly, nor would the spilling of intestines and gore. If it did, then I might as well give up being a doctor. Eating a raw, warm rabbit, though . . .

He lifted the first rabbit in His left hand while He thinned His right fingers and slid the tiny tips into the game, loosening the hide from the inside. The animal peeled, literally, like a banana. He did the second one the same way, then set to devouring them before they could stiffen and freeze. He took large bites of the greasy flesh, blood dribbling down His chin, until He had consumed everything but the bones and the fur that He had previously skinned off. He hardly seemed to chew the food, but bolted it down in an effort to finish the unpleasant business as swiftly as possible. “Okay,” He said, standing and wiping the mess from His cheeks and lips. “Time to go.”

His eyes glittered.

My stomach flipped like a dying animal looking for a cozy place to have that final wrenching spasm, despite my concentrated efforts to control myself. I turned and led the way this time, for the snow under the trees was considerably less than it had been in the open and in the less dense sections of the woods. As I walked, I tried to sort out the confusing mass of conflicting emotions throbbing through my brain. He was the greatest boon to mankind in centuries, was He not? Of course He was I Look at the power in His hands, the ability to heal that burned in every cell of His body. This was not just a steam engine or an electric lightbulb or a more powerful rocket booster that had been discovered; this was a panacea for all that physically ailed the race. I should discount little things like His wild appetite, His energetic consumption of the rabbits—blood, guts, and all. Shouldn’t I? Of course I should. Only a small-minded man will overlook intrinsic worth because of superfluous surface defects.

The wind blew.

The snow beat my face.

Cold . . .

But there was one thing troubling me: Yes, perhaps He was benevolent in His previous stage when I had

kidnapped Him, when He had brought the explosion and fire victims back from the dead. But did that necessarily mean He would look kindly upon mankind in one of His later stages, after He had changed?

Wouldn’t we seem very inferior? And sort of pitiful. And maybe worthless. And, just maybe, pests to be dealt with out-of-hand?

I shivered.

Damn! I was acting like some superstitious child, or some senile old ninnie. This wasn’t a retelling of the hoary Frankenstein tale! My artificial human was not going to turn on me like a senseless brute and bash my head in. I shook my head and tried to dispel any more such thoughts. I knew they were unhealthy.

Thirty-five minutes later, we came out of the trees to the edge of the foothills. We had taken off our snow-shoes when we had entered the last woods, now we unstrapped them from our packs and put them on again. I made a mental note to be especially careful if we encountered any drifts. We couldn’t afford another two-hour delay while He shoveled me out with His hands. It would be dawn before we reached the cabin now, and I didn’t want to stay out in daylight any longer than was absolutely necessary. We moved across the barren slopes, and we had just crested the rise when the sound came to us.

“What is that?” He asked, taking my arm and stopping me.

I peeled off my mask and waited. It came again, low and hollow. “Wolves,” I said. “A pack of wolves.”

IV

We stood a third of the way down the next slope, nothing behind which we might hide, no trees to climb, nothing at all to do but wait and hope that they passed us by, crossed another hill, went down a distant ravine and never knew our presence. But my scalp tightened and cold chills crept up my spine, flushing through all parts of my body when I considered the unlikelihood of that. A wolf is a formidable opponent. It has exceedingly sharp senses, among the keenest in the animal kingdom. And with the wind blowing our scent in the direction of the guttural, melancholy howls, there was almost no chance at all that we would escape detection.

“I’ve read only a little about wolves,” He said. “But they are vicious, very vicious, when they are hungry and hunting. Am I right?”

“Too right,” I told Him, drawing my pin gun and wishing, now that I was going to have to face beasts instead of men, that I had something more lethal than narcodarts. It had been a harsh winter; I could tell that from the depth of the drifts, the bow of the trees after they had borne so many weeks of heavy snow. The wolves had been driven out of the higher levels of the park, down from the dense upper forests into the more civilized areas. Food would be scarce up there in this weather. Farther down, there was still good hunting . . . “They must have caught the odor of blood—maybe from the rabbits you skinned. If that’s the case, they’ve been searching for some time now, and they’re bound to be n

ear mad with excitement.”

Just as I finished, the first wolf loped into sight, a scout of the main pack. He came over the brow of the next hill and stood looking at us across the little valley that separated him from us. His eyes were hot coals, feverish, gleaming between the beads of the snow curtain that draped the night. His muzzle quivered, and he bared his teeth. Two prominent fangs arched up from his lower jaw and shone wickedly yellow-white in the gloom, fangs that could rip out a man’s throat in seconds, free the bubbling blood in human veins. He danced backward, then forward again, examining us, his excitement growing by the second. Then he raised his head and dropped his lower jaw to howl.

I leveled my gun and fired a burst of pins that caught him in the throat. He gagged, shook his head, and toppled over. He writhed a moment, his legs kicking spasmodically, and lay still, sleeping. But the sounds of his comrades indicated little gap between the scout and the body of the main force. They would be on us in seconds. Their reaction to the limp body of their companion would decide our fate—whether they advanced for revenge or turned tail and ran. Somehow, the latter seemed unlikely.

The other wolves crested the ridge and stopped like a line of Indians confronting the cavalry in a cheap Western movie. They moved around uncertainly, taking turns sniffing the scout’s body. When they realized he was not dead but sleeping, some of their bravura was restored. They pranced around more lightly now, their feet hardly touching the ground, springing like wind-up toys—though their teeth were real enough. A few threw their heads back and let go some really wild howls at the low sky. The echo beat around the foothills, carried to the wall at the base of the mountain and boomed back in a loud whisper.

“What should we do?” He asked, though He didn’t seem very concerned—nowhere near as concerned as I was when I looked at those brutes.

“Let’s wait and see what move they make,” I said. “If we try to run, that might give them enough confidence to attack.”

Meanwhile, I counted them. With the scout, there were sixteen.

Sixteen.

I could swear it got colder and that the wind blew the snow more insistently than ever, but it may have been my imagination. Besides, I was sweating, a switch if ever I saw one. We waited.

They made their move. Three of the braver beasts started down the opposite slope, gained confidence and loped full speed across the small valley which they easily covered in a dozen strides. When they reached the base of our hill, I shouted, “Fire!”

We opened with our pin guns and stopped them before they were halfway up our hill. They kicked, jerked, went down in a tangle of legs, lay very still, the drugs doing quick work on them. One of them, the largest and most darkly-furred, snored.

The other beasts snorted and snarled among themselves, much like football players planning strategy in a huddle. They milled around, looking at each other, then at us, then back to each other.

“Maybe they’ll go away now,” He said.

“Not a wolf. For one thing, we’ve insulted them. A wolf is too proud a creature to give up without a fight. Besides, they look rangy, hungry. They won’t stop as long as they think they’ve found their supper. And that’s just what we must look like to them.”

Just then, four more wolves flashed down the slope and after us, snarling, foam flecking the corners of their twisted mouths, their eyes fierce and glowing like crimson gems. The attack was a surprise and launched with startling swiftness, almost as if they had mutually agreed to take us unaware. But our vantage point was too good, too safe. I brought the last one down only a dozen feet away from me. Just in time to hear the vicious growl behind us!

We whirled.

Two wolves had detached from the main pack and had slunk around behind us and had come up the back of our hill, almost in the footprints we had made. Now we were surrounded. I caught one with a narcodart burst as he leaped for me. He twisted in midflight, his entire body wracked with spasms as the drugs relaxed his mind and released his tense muscles from their constriction, draining the savage fury from him like a tap drains a keg. He crashed short of me by two feet, throwing up a spray of snow. He choked, tried to get up, and slammed back to the ground, passed out. The second wolf had come too fast and had landed on His shoulders, bearing Him to the ground and sinking teeth into His pseudo-flesh. Apparently, the pseudo-flesh, the cultured meat that was grown in the Artificial Wombs, was as good as regular meat, for the wolf did not draw back, but went after its prey in a frenzy.

It swung its head down to tear open my android’s neck. I fired a round of pins, but they rolled just then, and the narcodarts sank uselessly into the snow. The next moment, the beast’s teeth raked over the exposed skin of His neck, but did not sink in very deeply. Little rivulets of blood ran down His skin. I was searching for an opening, when He suddenly swung His fist against the side of the wolfs head and crushed its skull as completely as if He had used an iron mallet. He had evidently hardened His flesh into a hammer-like weapon, just as He had earlier shaped it into a scoop. The wolf gurgled once and fell off Him.

“Your face,” I said. His cheek had been badly chewed, and He was bleeding profusely.

“It’ll be all right.” Even as He spoke, the bleeding slowed and stopped. His cheek seemed to crawl with a life of its own, wriggling, shivering, pulsating. He reached up and tore away the flap of flesh the wolf had loosened. I could see, beneath, the welling brightness of smooth, new skin. In moments, there was no sign of His wound; He had healed completely. “The other six,” He said, indicating the last of our enemy.

But they were slinking off along the ridge, watching us carefully but with no apparent intent of attack. They had seen ten of their kind fall before us, and they had suddenly lost some of their pride—enough, anyway, to let them give up in hopes of finding easier prey.

“Let’s go,” I said, “before they change their minds and come back. Or before their comrades wake up.”

“Just a minute,” He said, kneeling before the wolf He had killed with His hand. He flopped it onto its back and began working on it. In a minute, He had skinned it as He had the rabbits. He tore large chunks of meat from its flanks and stuffed them into His mouth, ripping with His teeth just as the wolves would have ripped us had we not been too much for them.

“Wolf meat should be stringy,” I said inanely.

“I need it,” He answered. “I don’t much care about the taste or the texture. The changes are accelerating, Jacob. I’ll only be a few minutes here.” He swallowed noisily. “Okay?”

“Yeah. Sure.”

“Good,” He said.

He continued cramming the bloody meat into his mouth, swallowing it with the minimum of chewing. I guess He had adapted His digestive system in some way to handle what He was throwing at it. Such a bolted meal of raw flesh would have had anyone else retching for the next three days as the stomach cleansed itself. I would have given just about anything at that moment to have been able to X-ray Him, run tests on Him to see exactly what He had done to Himself. It was the doctor in me, the medical curiosity surfacing even while wolves stalked in the night and World Authority police ranged somewhere behind, closing the gap. Ten minutes later, He had devoured most of the animal and was ready to go.

We walked down the slope and across the wolf-strewn valley.

I kept looking behind, expecting the flash of teeth, a guttural snarl, ripping claws.

It was going to be a bad night . . .

An hour and forty-five minutes after dawn, afraid every minute that we would be seen and apprehended even though the park seemed deserted, we reached the cabin. The sight of it filled me with the first warmth I had felt since the wolves had set me to sweating inside my bulky insulated clothing. The place was as I remembered it, a comfy nook nestled in a grove of pine trees with its back door facing a sheer cliff and its front door giving view to a breathtaking panorama of snow and trees and gentle foothills. It was not the sort of place a hardy outdoorsman would go to rough it. Harry and

others like him paid well for the modern conveniences in the trappings of rustic simplicity.

I had no key this time. Even if I had thought of coming here right from the beginning, I would not have gone to Harry and implicated him by getting a key. This was my folly, and I would have to bear all the grief and punishment if things fell down around my head. I had to break a pane of glass in the door, fumble around for the inside latch, all the time wondering when someone would come running into the living room shouting, “burglar,” and wielding a twenty-gauge shotgun. But the place was empty as I had imagined it would be.

Inside, we found a cardboard box and used one of the sides to cover the hole I’d made, thereby keeping out the worst of the wind. I plugged the heaters in after He started the generator in the attached utility shed to the rear of the cabin, and I thanked the gods that Harry had electric heaters as well as fireplaces. The fireplaces would give off smoke that would have every World Authority ranger and copper down on our backs inside of the hour. The electric jobs would keep the living room sufficiently warm and the remainder of the house just comfortable. And that was sufficient. We could not expect total luxury in our position. This little bit of peace and quiet and rest, after our days and days of running, did seem like total luxury. The heavy, whining noise from the generator would have to be risked. It was well-muffled, and if anyone got close enough to hear its low whumpa-whumpa, then chances were they were already suspicious and investigating the cabin.

“Good,” I said, watching the coils begin to glow inside the heaters and feeling the first warm drafts of air as the blowers came on.

“The food,” He said. “I want to see what I have to work with.”

“This way,” I said, taking Him down into the natural icebox of the cellar. There was very nearly a whole cow hung from meat hooks embedded in the ceiling. The meat was frozen solid and filmed by a thin coat of fuzzy frost. It was most probably a tank-grown cow, but the meat would still be tender and tasty. The walls of the room, natural rock, were coated with thick, brown-white ice, as was the floor. The cellar had been carved directly from the base of the mountain for the purpose of food storage; it was a fine job.

Zero City

Zero City Freedom Omnibus

Freedom Omnibus ACrucible of Time

ACrucible of Time Something MYTH Inc

Something MYTH Inc Forbidden Land

Forbidden Land Corridor of Storms

Corridor of Storms The Peytabee Omnibus

The Peytabee Omnibus Beyond the Sea of Ice

Beyond the Sea of Ice The Time Of The Transferance

The Time Of The Transferance EarthBlood

EarthBlood The Lexal Affair

The Lexal Affair The Web

The Web Slave Ship

Slave Ship Eternity Row

Eternity Row Planet Pirates Omnibus

Planet Pirates Omnibus Aztec

Aztec The Awakening

The Awakening Aztec Blood

Aztec Blood The Mystery of Ireta Omnibus

The Mystery of Ireta Omnibus Aztec Autumn

Aztec Autumn The Savage Horde

The Savage Horde Anti - Man

Anti - Man Deep Trek

Deep Trek Starfall

Starfall The Paths Of The Perambulator

The Paths Of The Perambulator Fool's Fate

Fool's Fate Jinian Stareye

Jinian Stareye Endurance

Endurance Spellsinger

Spellsinger Hybrids

Hybrids Beyond Varallan

Beyond Varallan Doona Trilogy Omnibus

Doona Trilogy Omnibus In th Balance

In th Balance Planerbound

Planerbound The Nightmare begins

The Nightmare begins Humans

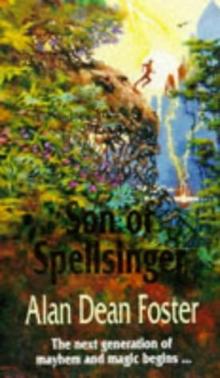

Humans Son Of Spellsinger

Son Of Spellsinger