- Home

- neetha Napew

Corridor of Storms Page 3

Corridor of Storms Read online

Page 3

He blinked and strained to see. Aar’s heart was thumping beneath his left palm. The dog saw it too—what Karana knew he could not be seeing. That thing was man and beast! It was the creature he had heard howling in the winter dark long ago, when he had huddled with the other children, waiting to die, to become food for ... the wanawut. Spirit Sucker. Beast of flesh and cloud and darkness, born to feed upon the People, born to teach the People the meaning of fear.

Karana gulped. His mouth was dry. The words of the magic man moved through his mind. Fear. He knew it all too well. The creature was close now, too close.

Illuminated by the starlight, it passed immediately ahead and to his right. It walked upright with a cautious, yet oddly rolling gait, bending slightly forward, like an aging man with a bad back. In the darkness it seemed to be clothed, for it was thickly maned across its shoulders and along its spine, and its entire body was darkly furred, with shaggy guard hairs of gray that gave it a frosted appearance. Its massive neck sloped into equally massive shoulders from which long, muscular, shaggy-haired arms swung with what, in a man, would have been considered easy grace. Impossibly, Karana saw that its hands were the hands of a man, except three times the size and clawed.

Staring upward out of the thick, deep lakes of shadow between the clumps of grasses in which he cowered, Karana saw the beast’s out slung bearlike profile. He caught glimpses of its features: a flattened, sloping cranium, a projecting brow, a flashing eye, a cylindrical muzzle, a wide, flaring, hairless nostril, a large, slightly pointed, grotesquely manlike ear set low at the side of its head, and a broad-lipped mouth that was pulled slightly back to reveal glistening, protruding canines that were longer than the boy’s dagger.

Karana felt sick. The teeth of the beast were unmistakably the stabbing fangs of a carnivore. Coupled with its narrow hips and bunch-muscled, relatively short-boned thighs, they marked the creature as one that leaped upon its prey.

It paused for a moment. Karana’s breath caught in his throat. His heart, like the dog’s, was pounding so hard that he was certain the beast had heard it. But if it had, it gave no sign of it. It seemed to be resting as it turned its head and stared in the direction from which it had come.

Then, after only a few heartbeats, it moved on again, and Karana heard the deep, effortless suck of its breath and the soft pad of its broad, toed feet as it moved on between the tussocks. But its scent, like his own, was tangled in the gentle eddying wind of the night, mixed into the smells of crushed grass and bruised tundral earth, so that neither boy nor beast smelled more than only the vaguest inference of the other as the creature moved away into the darkness.

Karana nearly vomited with relief. Then, beside him, Aar shivered, and the boy saw that from the distances out of which the beast had come, others of its kind were coming toward him. He held his breath and gripped his dagger and the dog more tightly as, one by one, stooped, bearlike shadows as hairy as mammoths walked past him.

None was as large as the first beast that had passed. Some were much smaller. One limped badly. It was totally gray and so grizzled that it was almost white; from this, and from the strained, ragged suck of its breath, Karana knew that it was old and injured. As it moved past him, he grimaced with revulsion at the sight of hairless, unpleasantly human-looking breasts swinging pendulously against its shaggy chest and was puzzled to see that one of its scrawny, patchy-furred arms was linked through that of a powerful silver-backed male, as though the stronger were actually being solicitous of the weaker. The boy was immediately struck by the incongruity of their behavior and troubled by the realization that, among many of his own kind, the weak and the old were not coddled or cared for; they were abandoned. Memories of dying children and his own abandonment surged through him. As they passed, Karana observed that the long, hairless fingers of the old female were laced through those of a much younger member of her gender, who was suckling an infant as she walked on the old creature’s other side.

For an instant the eyes of the suckling met those of Karana. Pale eyes. Filled with starlight. As clear as new ice upon which no snow has fallen.

The boy was stunned by their clarity and their undeniable but unexpected beauty. Then terror struck him. Had the thing seen him? Had it picked him out from the shadows? He squeezed his eyes shut, deliberately breaking visual contact with the suckling, knowing that if it recognized him as a living being, it had only to loose its lips from its mother’s hideous teat and, through sound and gesture, indicate his presence to the others. Even with Aar ready to leap to his defense, neither he nor the dog would survive long.

But the thing kept on sucking. Its eyes were the wide, vacant, glossy eyes of the newly born, empty of all but starlight. Karana knew it was carried past him in the fold of its mother’s hairy arm when he heard the soft whispering of her footsteps in the grass directly ahead of him.

Then, after a while, all was quiet except the hammering of his heart. Cringing with fear, he opened his eyes. With infinite caution he peered over the top of the grasses to see that the last of the beasts had gone by him, trailing southward. For a long while, exhausted by fear, the boy and dog remained motionless and silent. Until Torka came up from behind them. And although Aar’s tail began to thump, Karana nearly leaped out of his skin in terror.

“I tell you, Karana, I have seen nothing.” Once again, as when he had addressed the boy within the encampment, Torka’s voice was stern with admonition. He stood frowning down at him in the darkness. “This country is crossed and recrossed by the fresh tracks of many beasts. Since Torka disregarded the advice of others and came out from the encampment in search of you and Brother Dog, this man has found it difficult to pick up the trail of one small boy amid the spoor of so many animals.”

“But they were there! An entire pack of them! They came from the north and walked to the south, into mammoth country at the base of the distant hills. And they trod so lightly, it seems now to this boy that they deliberately laid no trail by which they might be followed. They—“

“Karana has seen only the flesh of his fear. Karana’s arrogance and overconfidence have led him to see things that are not there. Torka says that this is good. Karana should be afraid. This man did not know whether he would find you alive or dead! Since Karana has cared nothing for the fear that his action has brought to others, it is time that he learns to fear for himself. Perhaps he understands why it is not good to challenge one’s elders and then to run off alone, where no man can stand with him against the predators concealed within the night.”

Karana was on his feet, facing the man, shaking his head in angry defense of his claim. “They were not concealed! I saw them. They were as close to me as you are now. I saw the wanawut! They were ugly and hairy and—“

The boy suddenly found himself seated again as Torka shoved him so hard that he knocked him down. A startled Aar jumped aside, ears back, as Karana, flat on his buttocks, his legs splayed and his mouth agape, stared up in befuddlement at the man he loved more than any other in the world. He could not understand what he had done to make Torka angry enough to strike him.

Torka shook his head at the boy’s obvious confusion. “Can Karana have forgotten that among Torka’s people it is forbidden to speak the name of a thing without respect? To do so is to dishonor the life spirit of that thing. And life spirits have wills of their own, be they the spirits of men or beasts, of stones, clouds, the smallest biting fly, or of Mother Below or Father Above. A dishonored spirit can become a crooked spirit—half flesh, half phantom—and who knows what such a spirit will do if it decides to punish the one who has shamed it? Torka says it is bad enough to be alone on the tundra with a foolish boy who has put himself at risk because he cannot control his temper, but it is worse to be alone with a boy who cannot control his tongue. Much worse. And much more dangerous to both of us!”

Karana closed his mouth. He looked up repentantly, knowing that Torka was right. The boy had forgotten the age-old taboo; it was a proscription among Torka’s

people, not among his own. It was easy to forget that they had not always lived together as father and son, that they were not of the same band.

“This boy meant no offense to Torka or to the spirits,” he apologized.

The eyes of man and boy met and held. Torka nodded. His lean, handsome features relaxed as he offered a conciliatory hand to the boy. “It was wrong of me to strike you.”

“It was wrong of me to run away,” Karana admitted, gratefully taking Torka’s hand and allowing himself to be pulled to his feet. “But Supnah’s camp is a. bad camp. This boy says that Torka’s people should not stay there.”

“Torka’s people? I am one man, Little Hunter. One man, with a woman and a newborn daughter to care for. Where should Torka lead his ‘people’? Into the unknown, where they would be alone and vulnerable again?”

“Torka has Karana. And Aar. He would not be alone.”

“But Supnah is your father. His people are your people. Would you truly wish to be parted from them again?”

The question altered the boy’s mood. Sullen hostility darkened his expression and thickened into bitterness. “Torka has forced Karana to dwell in the hut of Supnah. This Karana has done—to please Torka, not because Supnah has asked it. But Supnah and his people fed Karana’s spirit to the wind, and this boy will not give it back to them. What they threw away, Torka has made his own. With his own mouth, Torka has called Karana son. And so now Karana says that he has no father but Torka. We are of one band. Forever.”

The words touched Torka, and he grasped the boy’s shoulder, wanting him to know it. “And so it is that for the good of Karana, my son, and of Lonit, my woman, and of little Summer Moon, my newborn daughter, that Torka says that we must all be of Supnah’s band now—forever, if he will allow it—because alone upon the tundra we are prey to our darkest and ugliest fears, and even the strongest man soon grows weak when he is beset by dread. Within the protection of a band, even the weakest man may dare to be brave and strong.”

Karana shook his head. “Supnah’s band is a bad band. And Navahk has always been a bad man. And the wana—I mean, the beasts that I saw in the night were there. This boy saw them.” “As Navahk has seen them.”

“Navahk is a liar. He has seen nothing.”

Torka’s dark brows came together across the high, narrow bridge of his nose. Far to the east the sun was rising beyond distant, glacier-smothered ranges. The faintest banding of light had appeared atop the mountains and was spilling over the ridges like mist, thinning the darkness just enough so that he could make out the intensely drawn face of the boy. Not for the first time, he was aware of Karana’s marked resemblance to the magic man, but his awareness vanished as he saw how haggard the boy looked.

“Come,” he said gently. “We must go back now. Lonit worries about you. When I left, little Mahnie, the daughter of Grek, was sitting with Pet, your sister, and both were crying from fear that you would be eaten by wolves.”

“Pet is not this boy’s sister! And Supnah’s camp is a bad camp.”

“When you are a man, you will understand that we sometimes must do what we do not wish to do—for others, not for ourselves.” He let the words settle quietly, watching as the boy’s face worked against them. Karana troubled him in many ways. He was headstrong, defiant, and often acted without thinking. But he always told the truth as he saw it. And sometimes in his dreams or with that strange sense that others did not possess, he did see things that others failed to see. Sight .. . sound .. . taste .. . touch .. . scent .. . these tools Torka shared with the boy. But not the sixth sense, that other, undependable, not-always-trustworthy power of knowing that was driving Karana to disobedience now.

Torka’s hand patted his shoulder encouragingly. “No band is without dissension among its members from time to time, Little Hunter. And fear takes many shapes in the dark. Look now to the east, into the face of the rising sun, and tell this man that what walks there could not have passed you in the night.”

Karana glowered. He saw tall, shaggy, reddish-brown humps moving on the horizon, tusks extended like branchless, horizontal trees. “Karana knows a mammoth when he sees one,” he retorted, his feelings hurt by Torka’s unwillingness to believe him. “They are not what I saw!”

“Then when you return to the encampment, you must tell the People that you have shared Navahk’s vision. And that what he has seen has been a good thing for his people—a warning for them to be wary of the spirits that walk hungry in the night.”

“Men must always be wary of the night. And this boy will never speak to Navahk.”

“Hard words for a boy to utter. Karana should know that when he ran off from the encampment, Navahk asked the People if what was given to the spirits should be allowed to come back to live as flesh in the world of men again.”

“Karana is not afraid of Navahk!”

“Karana had better be—for Torka’s and Lonit’s sake, if not for his own! This man has named you son! If you are put out of Supnah’s band, I will not be able to watch you walk the wind alone. I will have to walk with you. Lonit will take our baby and insist upon walking with me. And soon she and I and our daughter and even you, Karana, will die upon the tundra, prey to lions or bears or wolves or simply to our own mistakes—all beasts every bit as terrible as the nightmare shapes of the wanawut that you claim to have seen.”

Sobered, Karana frowned. “We tried to live among another band before and were forced to walk away alone. Has Torka forgotten how it was? How Karana said that we must go from the mountain cave where we lived with the people of Galeena? How Karana said that the mountain was a bad place and that Galeena’s band was a bad band? Torka would not listen. But it was as Karana warned. And so at last we fled when they tried to kill us, and, as in Karana’s dreams, the side of the mountain fell to bury the cave forever, and within it Galeena and all his people died. But we have survived—alone.”

“Barely, and always at the risk of death.”

“Then do as Supnah says. Become a magic man! Let Navahk be the one to walk the wind.”

“No, Karana. Torka will not assure his place within the band at the cost of another man’s life. What I have said to Supnah, I say to you:

Torka is a hunter. No more.”

Karana clamped his mouth tight against frustration. Torka was talking to him in the kind, condescending tone that adults often took with recalcitrant children.

Aar nuzzled his hand, to remind him that it was time to break the long hunger of the previous night. And from the west Supnah was trotting toward them with his spear raised in greeting and his voice crying out the boy’s name with joy and relief.

Beyond the eastern ranges the sun was rising quickly now. Its face was still hidden, but its light had absorbed the stars and washed away the darkness. The night seemed long ago, its terrors muted by fatigue and distance. Karana sighed. If he had been wrong to run away, perhaps his sight had been equally in error? Perhaps he had grown confused in the darkness and, looking east instead of south, had only seen mammoths after all?

The tattooed woman smiled. She was as big and as brash as a man, but it was impossible to see her clearly, even though the sun was well up and the tundral world was awash in the sweet, yellow light of the spring morning. Like the other women of the band, she was armored against biting flies, in warm-weather leggings and a lightweight tunic of caribou skins that covered most of her body; but unlike the other women, every visible inch of her skin was blackened by tattoos.

Eyelids, lips, nostrils, earlobes. Even her filed teeth, fingernails, and the palms of her hands were covered with a maze work of dots and slashes that formed a blur of intricate, circular designs—unwanted gifts inflicted upon her by the tattoo-loving Ghost Band, to which she had been enslaved since girlhood. Then Torka, with the aid of Supnah and his hunters, had rescued her.

Now she knelt outside Torka’s shelter, happily helping his woman, Lonit, to pound fat into oil that would be used to saturate the bundles of moss that lay at their

sides. These would later serve as wicks for tallow lamps of hollowed stone and, in the days of the long dark, would light the pit hut of Torka during hours of endless night. The tattooed woman enjoyed both the work and the prospect of light in the winter dark, so she smiled; but because her teeth were as black as her face, her smile went unseen as she spoke with emphatic optimism.

“Aliga says that Torka and Supnah will soon return with the boy. Lonit will see. The spirits seem to be with Karana. His talk to the magic man was bad talk, but he is the headman’s son, and Supnah is so glad to have him back, no harm will come to him because of his runaway feet and tongue.”

“It is not Supnah whom Karana should fear. It is Navahk.”

Lonit’s long, graceful hands did not slow as she spoke. “This woman does not like the way the magic man looks at the boy or the way that he looks at me ... or the unspoken words that hide behind the things he says to Torka.” Her beautiful, delicately formed features were grimly set as she pounded and scraped at the wedges of fat, using the grinding stone that she held in her fist to crush them within the concave mortar.

Aliga, the tattooed woman, envied Lonit not only for her beauty, which was unmarred by tattoos, but because she had a man to work for and worry over. A man beside whom most other men, including the powerful headman, Supnah, seemed inconsequential.

Torka!

Aliga’s heart always beat a little faster when she thought of him. Until she had seen Navahk, the magic man of Supnah’s band, she had not thought it possible that a more physically striking man than Torka could exist.

But Navahk existed. Navahk! In his fringed clothes of white, with the single winter-white flight feather of an Arctic owl braided into the forelock of his shining, knee-length hair. Navahk! With a face as finely made as a stallion’s and eyes as black and lustrous as an obsidian dagger. That one, like Torka, could have any woman he wanted. He would never look at Aliga; and yet if he did focus his magic eyes through her tattoos to the substance of the woman beneath them, she would look back boldly and let him see how her heart quickened for him. He would know that he was the only man capable of shadowing Torka in her eyes.

Zero City

Zero City Freedom Omnibus

Freedom Omnibus ACrucible of Time

ACrucible of Time Something MYTH Inc

Something MYTH Inc Forbidden Land

Forbidden Land Corridor of Storms

Corridor of Storms The Peytabee Omnibus

The Peytabee Omnibus Beyond the Sea of Ice

Beyond the Sea of Ice The Time Of The Transferance

The Time Of The Transferance EarthBlood

EarthBlood The Lexal Affair

The Lexal Affair The Web

The Web Slave Ship

Slave Ship Eternity Row

Eternity Row Planet Pirates Omnibus

Planet Pirates Omnibus Aztec

Aztec The Awakening

The Awakening Aztec Blood

Aztec Blood The Mystery of Ireta Omnibus

The Mystery of Ireta Omnibus Aztec Autumn

Aztec Autumn The Savage Horde

The Savage Horde Anti - Man

Anti - Man Deep Trek

Deep Trek Starfall

Starfall The Paths Of The Perambulator

The Paths Of The Perambulator Fool's Fate

Fool's Fate Jinian Stareye

Jinian Stareye Endurance

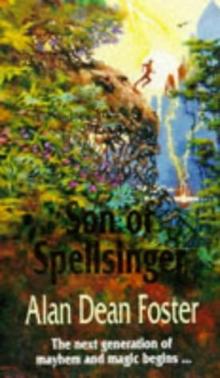

Endurance Spellsinger

Spellsinger Hybrids

Hybrids Beyond Varallan

Beyond Varallan Doona Trilogy Omnibus

Doona Trilogy Omnibus In th Balance

In th Balance Planerbound

Planerbound The Nightmare begins

The Nightmare begins Humans

Humans Son Of Spellsinger

Son Of Spellsinger