- Home

- neetha Napew

The Web Page 2

The Web Read online

Page 2

sian or whatever—I don't even have the words for it. Maybe Paul would. But

the three of us—we've come this far together. And that means something."

Rourke checked the oxygen. The cowl flap switches were open. He set the

fuel selector valves to "main," the induction air system to "filtered."

Visually, he surveyed the circuit breakers and switches; there wasn't time

for a full check. He flipped the battery switch to "on."

Glancing at the main and auxiliary fuel indicators, he started throttling

open, the prop controls at low pitch. He adjusted the mixture

controls—full rich. He checked the auxiliary fuel pump; it was registering

high. He switched it off.

Glancing out the cockpit storm window again, he hit the magneto/start

switch.

"Paul—up here with a gun!"

Already, Rourke was exercising the props, watching the rpms build. He

throttled out, checked the magneto variances, throttled again. "Little

late to ask—the wheel chocks gone?"

"Yes." She smiled, laughing for an instant.

Rourke nodded, feathering the props, the mob less than a hundred yards

away now, the Chevy pickup closing fast. There was no glass in its

windshield, and men, packed in its truck bed, were firing rifles and

shotguns.

"Paul!"

"Right here."

Rourke glanced behind him; the younger man held Rourke's CAR- in his

right hand; his left was pushing the wire-rimmed glasses back from the

bridge of his nose.

"Put a few shots out the storm window," Rourke ordered. Then,

concentrating on getting airborne, he

ignored the mob. Trim tabs, flaps—he set them for takeoff.

He released the parking brake. "Let's get the hell out of here," Rourke

almost whispered.

"Brace )ourself Paul—and keep shooting." For the last ten seconds, pieces

of hot brass had pelted his neck and shoulders—Rubenstein firing the Colt

assault rifle toward the mob. The younger man stood almost directly behind

him.

Rourke glanced at the oil temperature, then rasped half to himself, "Full

throttle—God help us."

He checked the fuel altitude setting as he released the brake. The

aircraft was already accelerating. "Buckle up, Paul," Rourke ordered. More

of the hot brass pelted him, then suddenly stopped. Above the roaring of

the engines there were sounds now of gunfire from the field, of

projectiles pinging against the aircraft fuselage.

"What if they hit something?" Rubenstein called out.

"Then we maybe die," Rourke answered emotion-lessly. He checked his speed;

through the cockpit windshield the runway was blurring under him now. The

Chevy still came, gunfire pouring from it, the mob suddenly far behind.

The pickup was closing fast.

Rourke checked his speed—not quite airspeed yet. The far chain-link fence

at the end of the airfield was coming up—too fast. More gunfire; the

pilot's side window spiderwebbed beside Rourke's head as a bullet impacted

against the glass.

And Rubenstein was firing again as well, having ignored Rourke's

admonition to strap in. The Chevy swerved; one of the men in the truck bed

fell out onto the runway surface. The gunfire was heavier now, sparks

flying as Rubenstein's . slugs hammered against the pickup truck's

body.

"Hang on!" Rourke worked the throttles to maximum, starting to pull up on

the controls—a hundred yards, fifty yards, twenty-five yards, the nose

starting up. Rourke punched the landing-gear-retraction switch, and as

they cleared the fence top, the pelting of hot brass against his neck

subsided, Rubenstein's gunfire having ceased.

"Thank God." Rubenstein sighed.

"Hmmm." Rourke worked the controls, opening his cow] flaps, trying to

climb, gunfire still echoing from below and behind them.

He checked his airspeed—not good enough—then began playing the cowl flaps

and the fuel flow. The airspeed was rising. As Rourke banked the aircraft

hard to port, Natalia leaned half out of her seat, across his right

shoulder, Rubenstein to his left. The Chevy, now far below them, had

stopped. The men with rifles and shotguns in the pickup's bed were now

minuscule specks, more a curiosity than a threat.

"Can I breathe now?" Paul Rubenstein asked.

Smiling, Rourke checked the oxygen system on the control panel, then

nodded. "Yeah." Rourke decided to breathe, too. . . .

The controls vibrated under Rourke s hands as he sat a)one in the

cockpit. Natalia had gone ah with Paul, to help him resecure some of the

gear that had jarred loose during the overly rapid takeoff. The airfield

tower had given him the weather—generally good, moderate winds, perhaps a

few thunderheads, but at low elevations and unlikely to be encountered.

Rourke looked below the craft now, its shadow stark and black against the

empti-

ness that he saw. That expanse of wasteland had once been the Mississippi

Delta region. Now, like the rest of the Mississippi valley from where New

Orleans had been to its farthest extent north, the ground was a

radioactive desert.

The Night of the War . . . Rourke could not forget it, and at last

lighting the small dark tobacco cigar that he'd had clenched in his teeth

for nearly an hour, he thought more about it. The anger of the men and

women in the mob back at the airfield, even the reluctance of Reed to risk

an American life to save a Russian life, no matter how valuable, how

good—it had all started then, on the Night of the War.

The global fencing—the saber rattling—had ended long before anyone had

realized and the nuclear weapons had been unsheathed and ready. The death

... all of the death in that one night, millions of lives lost. The

pounding of nuclear weapons, which here, below him, had produced an

irradiated vastness that would be uninhabitable for perhaps as long as a

quarter-million years, had struck along the San Andreas fault line and

brought about the feared megaquakes—but far worse than anyone, save the

most wild speculator, had ever imagined. Much of California and the West

Coast had fallen into the sea—more millions of deaths. The Soviet Army—the

Soviet Union itself—was nearly as crippled as was what had been the United

States. The invading Soviet Army, headquartered in neutron-bombed Chicago,

had set up outposts in surviving major American cities and industrial and

agricultural regions, outposts that not only contended with the growing

wave of American resistance, but with the Brigand problem. Rourke felt a

smile cross his lips as he exhaled the gray smoke of his cigar. Some-

thing in common with the self-styled conquerors—the Brigand warfare, the

pillaging, the slaughters.

For it was after the war that both the best and worst of humanity had

risen to the fore. The best—Paul, certainly. The young Jewish New Yorker

had never ridden anything more challenging than a desk, never fought

anything tougher than an editorial deadline. Now, in the few short weeks

since the world had forever changed, Rubenstein had forever changed as<

br />

well. Tough, good with a gun, as at home on a motorcycle as he had been in

a desk chair. Even in the short period of time that had elapsed, Rourke

had noted the definition of his musculature, and the different set to the

eyes he continuously shielded behind wire-rimmed glasses. The wonder, the

excitement, were all there as they had been from the first with each new

challenge; but there was something else— a pride, a determination derived

just from having survived, from having fought, from having surmounted

obstacles. In those few short weeks, Rubenstein had grown to be the best

friend Rourke felt he had ever had— like a brother, Rourke thought,

feeling himself smile again. An only child, he had never been blessed with

a natural brother. But now at least he had one.

And Natalia—the magic of her eyes, the beauty that he would have felt

hopelessly inadequate to describe had the need arisen to do so. Rourke had

first met her before the war—a brief, chance meeting in Latin America when

she had worked with her now-dead husband, Vladmir Kara-mat sov. Rourke had

been a CIA covert operations officer; Karamatsov had been the same

thing—but for KGB, the Soviet Committee for State Security. And Natalia

had been Karamatsov's agent. Then, after the war, there was the staggering

coincidence of finding her,

dying, wandering the west Texas desert, herself the victim of Brigand

attack. The feelings that had grown between him and the Russian woman,

despite her loyalty to her country, despite her job in the KGB, despite

her uncle—General Varakov, who was the supreme Soviet commander for the

North American Army of Occupation. "Insane," he murmured to himself.

And then another chance meeting. Rourke had been pursuing the trail of his

wife, Sarah, and the children, lost to him on the Night of the War. Rourke

let out a deep breath, feeling the tendons in his neck tightening with the

thoughts. "Sarah," he heard himself whisper. The meeting—the meeting with

the girl named Sissy; the seismological research data she had carried

regarding the development of an artificial fault line during the bombing,

something that would reduplicate the horror of the megaquakes that had

destroyed the West Coast, but would instead now sever the Florida

peninsula from the mainland.

For all the destruction and the death, it had proven again that there

still remained some humanity, some commonality of species. For with

President Chambers of U.S. II and General Varakov, a Soviet-U.S. II truce

had been struck to effect the evacuation of peninsular Florida in the hope

of saving human lives.

The job finished, the truce had ended and a state of war existed once

again.

Rourke shook his head. War. Sarah had always labeled his study of

survivalism, his knowledge of weapons—all of it—as a preoccupation with

gloom and doom, a fascination with the unthinkable. It had torn at their

marriage, separated them, and now, despite the fact that they had promised

each other to try again for the sake of

Michael and Annie, for the sake of the love he and Sarah had always felt

for each other, it was war that had finally separated them.

Rourke remembered it; he hadn't wanted to leave, to give the lecture to be

delivered in Canada. Hypothermia—the effects of cold. The world situation

had been already tense; but Sarah had insisted, so she could get herself

together, to try again with him. It had been there, in Canada, that Rourke

had at last learned of the gravity of the situation rapidly developing

between the United States and the Soviet Union. He had been aboard an

aircraft nearly ready to land in Atlanta, near his farm in northeastern

Georgia, when he had heard over the pilot's PA system that the first

missiles had been launched. Then that night—the night that had lasted, it

seemed, forever, and nothing ever the same afterward.

He shivered from the memories: the crash after the plane had been diverted

westward, the struggle to survive afterward with the injured passengers,

the useless-ness of his skills as a doctor to the burn victims in

Albuquerque—then the slaughter of the passengers by the Brigands.

"Brigands," he murmured. He glanced at his watch; the black-faced Rolex

Submariner showed that he had been lost in his reverie for at least ten

minutes, perhaps longer. He checked the instruments, then the ground below

him—now a nuclear desert, a no man's land where once millions had lived,

worked, tilled the soil—nothing now. Not a living tree, or a blade of

grass that wasn't brown or black.

His cigar was gone from his teeth and he checked the ashtray, realizing

he'd extinguished it. Rourke shook his head, silent—tired. . . .

Reed started to stub out his cigarette, but didn't. Cigarettes were

getting harder to find. He kept smoking it, then looked up across the

littered table from his cup of coffee. "What, Corporal?"

"Captain, your pal, Dr. Rourke—he's gonna have trouble, sir."

"He had trouble—remember? Hell of a lot of good we were to stop it." He

looked back at the cigarette and noticed that the skin of his first and

second fingers was stained dark orange. Reed wondered what the stuff in

the cigarettes did to his lungs. He shrugged and took another drag; then

through a mouthful of smoke, he said, "What kind of trouble? He's got a

radio. We can contact him."

"A storm system—it just moved in, like it was out of nowhere, sir."

"He's a fine pilot. He'll fly over it," Reed answered, dismissing the

problem.

"But, Captain?"

Reed looked up at the red-haired young woman again. "What, Corporal?"

"You don't understand, sir," she insisted. "See. It's a massive winter

storm system—it was just there. You

know the weather's been crazy—"

"Winter storm system? Have you weather people ever figured out you can

learn a hell of a lot by just looking out the damn window?" Reed checked

his wrist watch, thinking of Rourke for an instant and envying Rourke the

Rolex he habitually wore. "An hour ago it was in the sixties—snowstorm?"

"Sir . . . please," the red-haired woman said.

"Yeah." He nodded, tired from going more than a day without sleep.

Standing slowly, he stubbed out the cigarette and looked around the

place—some officer's club, he thought. One lousy window. He walked across

the room, lurching a little because of sitting so long in one chair,

tired. He staggered against the back of a chair. A Marine lieutenant

started to his feet, saw Reed, then looked noncommittal. Reed shrugged it

off, reaching the window. "I need a good couple hours sleep, Corporal."

"Yes, sir." The red-haired woman nodded.

Reed pulled back the heavy curtain. Staring outside, he whispered, "Holy

shit!" He judged the depth, at least four inches of snow; a heavy wind was

blowing what had fallen back into the air. Drifts were mounting against

the tires of a jeep outside by the walkway.

"Yes, sir. That's it, sir," the red-haired woman echoed.

Reed looked at her. "It's impossible! It was like spring a few—"

<

br /> He looked back out the window. It was no longer like spring.

The sleet was coming in torrents now. Sarah huddled beside the children

under the overhang of rocks, a pine bracken to her right, as she stared

down into the valley. The pines made a natural windbreak for herself,

Michael, Annie, and the horses.

Across her lap, resting on her blue-jeaned thighs instead of the

children's heads, was the AR-—the one modified to fire fully

automatically when she put the selector at the right setting, the one

almost used to kill her the morning after the Night of the War, the one

she'd taken from the dead Brigand and used to shoot out the glass window

in the basement of her house in order to set off the confined natural gas

there after the gas lines had begun filling the house following the

bombing—to blow up her own home and the men inside it who had tried to

rob, to kill, to rape.

Priorities were odd, she thought, as she raised her left hand from Annie's

chest where it had rested and tugged the blue-and-white bandanna from her

own hair. Before the Night of the War—rape, it would have been a top

priority. But now losing things had somehow become unconsciously more

important as she considered life.

Rape would be a horror—but it could be overcome. Death—it might well be

more than expected. But to be robbed, deprived of food or horses or

weapons with which to fight—this was worse than death, and rape of the

spirit more foul than any rape of the body.

She looked to her right. Michael was sleeping, his body swathed—like

Annie's—in blankets against the bizarre and sudden cold. Michael would be

turning eight soon, and already he had murdered a man—a Brigand who had

tried to rape her.

She studied his face. It was John's face, but younger, though appearing no

less troubled. She could see the faint tracing of lines which in adulthood

would duplicate the lines in the face of his father. She could see the set

of his chin. She thought of his father's face, the quiet, the

resoluteness, the firmness. She found herself missing that—the steadiness

Zero City

Zero City Freedom Omnibus

Freedom Omnibus ACrucible of Time

ACrucible of Time Something MYTH Inc

Something MYTH Inc Forbidden Land

Forbidden Land Corridor of Storms

Corridor of Storms The Peytabee Omnibus

The Peytabee Omnibus Beyond the Sea of Ice

Beyond the Sea of Ice The Time Of The Transferance

The Time Of The Transferance EarthBlood

EarthBlood The Lexal Affair

The Lexal Affair The Web

The Web Slave Ship

Slave Ship Eternity Row

Eternity Row Planet Pirates Omnibus

Planet Pirates Omnibus Aztec

Aztec The Awakening

The Awakening Aztec Blood

Aztec Blood The Mystery of Ireta Omnibus

The Mystery of Ireta Omnibus Aztec Autumn

Aztec Autumn The Savage Horde

The Savage Horde Anti - Man

Anti - Man Deep Trek

Deep Trek Starfall

Starfall The Paths Of The Perambulator

The Paths Of The Perambulator Fool's Fate

Fool's Fate Jinian Stareye

Jinian Stareye Endurance

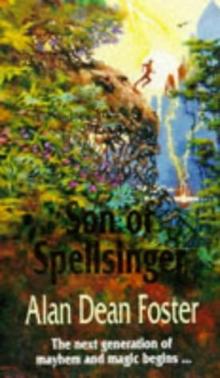

Endurance Spellsinger

Spellsinger Hybrids

Hybrids Beyond Varallan

Beyond Varallan Doona Trilogy Omnibus

Doona Trilogy Omnibus In th Balance

In th Balance Planerbound

Planerbound The Nightmare begins

The Nightmare begins Humans

Humans Son Of Spellsinger

Son Of Spellsinger