- Home

- neetha Napew

Forbidden Land Page 16

Forbidden Land Read online

Page 16

He nodded, satisfied. They must heed what he would say to them now. “I have listened in silence as Grek and Simu have argued. As they have argued, I have felt the anger of each man growing toward the other. Soon, if their words were allowed to continue, they would no longer think of themselves as brothers within this band.”

“We are not brothers!” Grek snorted.

“No!” affirmed Simu. “In this new land we must respect each other’s ways and differences. Grek has no right to say that Simu’s tale is wrong and that Grek’s tale is the only tale! We must remember that we are not originally of the same band. We have different customs, different beliefs, different—“

“But we are one band now!” Torka was emphatic. “One very small band. We must never forget that there is no greater magic, be it for good or bad, than the power of words. And so, since you have chosen to name me headman, now will you listen as I speak words that will be a magic that will make us strong together!”

Simu stared, obviously taken aback by the power and strength of purpose in Torka’s tone. “This man will listen.”

Grek clenched his teeth and nodded.

“Good. Hear me well, both of you. There will be no more words of anger among us as to who is right or who is wrong in matters that no man or woman can prove. Among the ancestors of Torka, neither Father Above nor Mother Below was first to be born. Rather was it said that male and female, earth and sky, together they were one beginning. And so I tell you now that we are one people who have shared the same beginning.”

He allowed the words to settle. The concept disturbed his listeners; they shifted uncomfortably in their bed furs.

Torka continued, “Just as the great herds that walk out of the face of the rising sun were once one herd, so were the People once one people, one band splitting into many, and the many dividing into many more until not one can remember the truth of the beginning. And so it must be for us now in this new land. This band must be one band, or it will be no band at all. No longer are you the people of Zinkh or the people of Supnah. Nor will you be the people of Torka, for someday this man will join Zinkh and Supnah to walk the wind forever, and in time no living men will remember our names.”

Within the hut there was silence. Outside, the wind moaned, wolves howled, and to the east, a mammoth trumpeted. Torka knew that Life Giver was near. The mammoth gave strength to the words that followed, and for all who heard them in the shadowed confines of the communal hut, they were magic.

“Here, in this Forbidden Land, from our combined pasts we will make one past. From our combined customs and laws, we will now set ourselves to find agreement upon one body of tradition by which we will live and by which we will grow strong. In the future, when differences arise, all will gather to reason them out until those concerned are satisfied. Never again will the men of this band lock horns like beasts, to fight as Cheanah and Torka once fought in the far land. From this day until days beyond our knowing, our children and our children’s children will sing the songs that our magic man shall create in honor of this new beginning! In this new land, in this dawn of our new beginning, no longer are we the men and women of Zinkh and Supnah and Torka. We are those who dare to walk into the face of the rising sun, and from this moment until the last moment of the world, we are one!”

Three days later, little Demmi awoke in the dawn crying: “Mother Below is waking up! Her skin moves! Her belly growls!”

In the thin light of a cold, cloudless morning, the naked child leaped to her feet, certain that the earth was about to swallow her and her people. The moments passed, and no one was eaten. But the people sat up as though a single sinew rope had jerked them from their dreams. No one seemed to be breathing as they leaned forward, their splayed hands pressing down upon the leather-and-fur covered floor of the hut. No one moved. No one blinked. Everyone was staring at Demmi.

She stared back. What was wrong? The men suddenly knelt and, bare backsides up, rested their ears against the floor while the women remained motionless, breathless.

Demmi, shivering now, was confused and frightened. “Is M-mother Be—“

“Shh!” Lonit silenced her.

And then, as one, Grek and Simu and Karana and Torka raised their heads and looked from one to another, and then to their women. As from one mouth, the hunters suddenly let out a hoot of pure joy. “Aieeay!”

The women clapped their hands and answered with little squeals of their own, and then everyone was hugging everyone else. Everybody scrambled to pull on their boots and shove themselves into their clothes.

“For Demmi will the first tongue be cut!” declared Torka, bundling her in his robe of lion skins, kissing her round little cheeks, and nearly smothering her with his hugs.

“Whose tongue?” queried Summer Moon, peeking up from where she still lay buried fearfully beneath her bed furs.

Laughter filled the hut, and Demmi found herself carried high on Torka’s shoulder as he took her outside, swathed in his own winter furs. His shoulder was warm and broad and firm beneath her bottom. The wonderful smell of his hair and skin enveloped her as he held her tightly with one big hand braced around the small of her back. Her little arms wrapped around the top of his head. She felt as if she rode upon the shoulder of Life Giver himself. “Look, Daughter! Look, everyone!”

Demmi frowned. All she could see was a great blur of dust on the eastern horizon. Then all the adults but Karana were whirling around and around, jumping up and down like excited children as they waved their arms toward the blur of dust.

The magic man stood apart from the rest, stark naked with Brother Dog at his right hand and Mahnie behind him. His handsome face was taut with cold; but his eyes were afire with pleasure. “Behold and rejoice! When the wind comes to us from the east, the people will know what we will hunt in the days to come!” he cried.

Puzzled, Demmi nestled close to Torka. Viewing only the distant cloud of dust, she saw no reason to rejoice. “We will eat dust?”

He laughed and shifted his weight. “No, my little one! Beneath the dust cloud to the east walk the great herds for which we have so long hungered. Soon we will eat meat-real meat—and Demmi shall feast upon the first tongue cut from our kills because she was the first to feel the herds moving upon the earth!”

The warmth of intense pleasure filled the little girl. “A baby could not do that!” she announced to all.

Far below her, in the tumbled, downwardly cascading canyons of the furs of Torka’s winter robe, Summer Moon looked up with envy as he said: “No, Daughter, a baby could not do that!”

By midmorning, the dust cloud was still far away on the high, mountain-toothed horizon. The wind had turned, and the overpowering stench of the herd was on the land—the smell of hide and antler, of slobbering muzzles nuzzling deep into the brittle remnants of the previous summer’s grasses, of urine and feces that reeked of chewed and digested lichens and mosses. The wind named the prey. Caribou!

Nevertheless, no one spoke the word. No one would dare to speak it until they had first praised it. To do otherwise would be an affront to the life spirit of the herd, and the animals might transform themselves into crooked spirits and become the hunters of men. Or they might turn away, and not even the oldest cow or weakest calf would consent to die upon the band’s spears.

Torka was the first to raise his arms. “Come now to the People!” he cried, offering to the forces of Creation a calling-forth chant that had been spoken by his people since time beyond beginning:

“Great bull,

Eater of moss,

Father of caribou children,

Feeder of the People since time beyond beginning,

Come now, come again to those who wait!

Follow the great cow,

Follow the caribou children,

Come now to feed the People!”

“I know this chant!” enthused Grek.

“And I know it,” Simu put in, as, together, the young hunter joined the old in the litany while Karana and

the women and children listened in wide-eyed amazement. The chant was one chant, and their shared knowledge of it proved that Torka had been right. In time beyond beginning the People had been one.

“Come, come now to feed the People!” the hunters chanted together, standing with Torka with their arms raised high. Karana joined them: “Come now to feed the People!” And now all four men of the band chanted as one:

“Great bull,

Great cow,

Little caribou children,

Lichen and moss eaters,

Come and we will share your spirit,

Come and we will be the wolves that make you strong!

Our spears are sharp

Our children are hungry.

Come!

That we may sing

Of your brave deaths

That will give life to this People!”

The chant ended. The days passed, spent in preparation for the hunt. The cloud was far away across miles of open country, beyond high hills and on the other side of a mountain pass.

“When will they come, Mother?” Summer Moon asked Lonit.

“Only they may know that, Daughter. They and the wind and the forces of Creation.”

By the dawn of the third day, although the rumbling in the earth continued, the dust cloud was no closer. The hunters, meanwhile, could find no fresh mammoth sign in the vicinity of the encampment. It was Karana, with Aar at his side as he sought a place of solitary meditation away from his people’s fires, who found Life Giver’s spoor far to the east.

“Life Giver walks ahead of us, out of this country, into the country of the caribou, it seems,” he advised upon returning to camp.

Torka nodded. Somehow he had known that it would be so. “Then it is time for us to leave it, too.”

And so at last they broke camp and, following the mammoth, walked eastward into the dawn as they sought to intercept and hunt the caribou.

They walked through softly blowing ground snow, across a world that seemed texture less substanceless, as though composed only of color and space: white land, gray mountains, blue sky. As they looked ahead the colors moved, shifted, and merged. Sometimes the sky was white; sometimes the earth was gray; sometimes the mountains were blue. Sometimes clouds touched the horizon. Sometimes, through the wind-churned, ephemeral clouds capes the land and the mountains appeared to float, disconnected from the world.

The days of storm had blanketed the steppe in snow. Thanks to the return of the wind, it was no more than two fingers deep in most places. But this had been a spring snowfall, so the huge, sloppy flakes that had managed to stick to the earth had frozen into solid ice when the bitter wind returned to blow across it. Travel was difficult, slippery, and slow despite the bone ice-creepers that they fastened securely with rawhide thongs across their boot soles.

Only the movement of the mammoth convinced them to go on—that and their dreams of sweet caribou steaks dripping over open fires; of thick, treasured winter pelts stretched on drying frames .. . and the fears that those steaks and pelts might disappear on the hoof before their little band reached the faraway hunting grounds.

The men steadied their steps with their spears, but when Torka suggested that the women do the same, everyone was appalled.

“It cannot be!” protested Simu.

“It has been forbidden for females to touch the hunting spears of men lest the male magic be sapped from them and they go limp!” Grek added, looking at Torka as though he could not believe the headman was unaware of this.

Torka was not unaware; there had been a time when he would have defended this belief with his life. “Did we not work together, man beside woman, to raise a shelter against the great storm even though the customs of our ancestors forbade this? And did the forces of Creation not smile upon our efforts and turn the wrath of the terrible wind away from us? Yes! And long ago, in the far country, when this man was alone on the winter tundra with Lonit and old Umak, it was Umak who, for the sake of our survival, put a spear in Lonit’s hand. It was Umak, a spirit master whom not even the most revered of shamans could equal, who taught Torka that when men are alone and faced with new situations, it is a good thing for them to learn new ways.”

Simu and Grek chewed the words as though they shared a cut of meat of questionable palatability,

By their reticence Torka knew they were not convinced. He nodded. The day was young, there were many miles to travel before nightfall, and there was game ahead for the taking. With these prospects before them, he would respect their hesitancy to break with the old ways. For now.

They walked until the day was nearly done. While the women and girls worked to dismantle the sledges and set up the night’s shelters, the men took up their weapons and spear hurlers and, with the dog bounding ahead of them, went out from camp.

They found nothing until Karana, walking with the dog well ahead of the others, pointed to a half-starved antelope, which lay quivering and panting in the cover of a broad span of tussocks. Well-hidden in the snow-dusted grasses, it was not much more than a sack of hide stretched over heaving bones. It must have been lying in the tussocks since before the last snowfall; no tracks had betrayed its hiding place.

The dog lunged in to harry it, and Karana saw the antelope’s head go up. The animal made pitiful “yuk-yuk” noises as it fought its way to its feet and stood on quivering stick legs. Its bowels went loose with terror, and it lowered its head and stared at the dog out of bulging eyes already clouded with approaching death.

Karana froze. Its gray eyes made him think of another animal ... of the gray-furred beast with eyes the color of mist—the wanawut—and in its arms he saw a human child and a half-human thing that called to him across the haunted miles. Brother! Do not abandon me! Brother! Do not forget me!

Immobilized by the vision, he was unaware of the others moving in for the kill until they were on either side of him, hurling their spears. The bone shafts hissed to their mark, and Karana came to his senses in time to praise the life spirit of the animal as it died, struck through the heart, belly, and throat by the spears of Torka, Simu, and Grek.

He felt foolish as he stood with his own spears still in hand while the others retrieved their weapons and sought to determine which spear had struck the killing blow.

“Torka!” announced Grek. “Torka has made the heart wound!”

Karana was aware of Torka eyeing him, asking him if he was well. “I ...” He hesitated, not really sure. The others were already working at the carcass, gouging out the eyes, opening the throat, cutting out the tongue. His stomach lurched—a loud, undignified growl that did not at all befit his status as magic man.

Torka made no pretense of not hearing it. “Come,” he invited. “We will share the eyes. Simu and Grek will take one, you and I will suck out the juices of the other. After all, you led us to this meat. It is as much yours as ours.”

Karana appraised the little animal. He was glad that Simu and Grek had removed the eyes—the gray eyes .. . the haunting eyes .. . the eyes that somehow spoke to name him Brother. Nevertheless, the sight of the carcass sickened him. “There is not much meat,” he said, feeling that he had to say something.

“Much or not much, meat is meat!” replied Torka.

“It is so!” affirmed Grek.

“And we’d be sucking bird bones from our women’s snares were it not for the magic power of your skill as a tracker, Karana,” added Simu. “Your eyes are quicker than this man’s spear, and a true thing it is when Simu says that it was our magic man’s Seeing gift that led us to this night’s feast!”

Feast? Karana allowed the word to pass without argument, although he knew that even under the most benevolent scrutiny, the little antelope would barely make a meal for twelve people at the encampment. Nevertheless, Simu’s praise made him feel better. He accepted it in silence, acknowledging it with a nod even though he knew that it was not through any magic gift of Seeing that he had sighted the antelope. Brother Dog had led him straight to i

t.

They gutted the little animal, shared its liver and eyes immediately, then stuffed its intestines back into its body cavity. Although the kill had not been from the herd of caribou, at Torka’s urging, they saved the tongue for Demmi, and the intestines, he had decided, would go to the other females.

“They have walked far this day,” the headman pointed out. Since his spear had inflicted the killing wound, he slung the limp carcass over his shoulder and, insisting that Karana walk at his side, led the others back to the encampment.

“And two of them with babies at breast!” added Simu with paternal and husbandly pride.

Grek nodded in stolid approval. “This man can tell that his woman’s hip aches. She deserves a special treat, and there is not much better than a sampling of fresh-taken gut to make a woman smile!”

They all agreed. The day had been long. They were tired. It was nearly dark, and the wind was bringing the scent of a cooking fire, which the women had raised in their absence, and of roasting ptarmigan and hare.

The females praised the kill and were kind enough not to remark that it was the only kill. Their men stood back with pleasure as the women and girls rejoiced in the intestines that the hunters had so unexpectedly elected to share with them. Demmi, whose pride shone brightly in her dark eyes, was given the tongue with a great show of ceremony by her father.

“And this most special portion of our kill is for Demmi, to honor her for being first to sense that which lies ahead of us, and thus to make this feast possible. Eat well and share of it what you will, for from this day you are no longer a baby in the eyes of this band!”

The girl, after eating the first sliver of flesh, shared her prize with Summer Moon, then the women.

Karana, watching them as they crouched together in a circle to divide these precious portions, was taken aback by the adoring look on Mahnie’s lovely face as she paused and looked up at him. Her eyes shone with pride. “My magic man has led the others to this kill!”

Karana looked down at her coldly, as if neither she nor her words meant a thing to him. if he allowed her to see his true feelings, she would know him for the deceiver he was; so he turned away, but not before seeing her face fall. Tonight he would seek solitude at the fringes of the traveling camp. He had walked as far as any man this day and had pulled his share of the weight of the sledges, but for reasons he could share with no one, he had failed to help his fellow hunters with the kill.

Zero City

Zero City Freedom Omnibus

Freedom Omnibus ACrucible of Time

ACrucible of Time Something MYTH Inc

Something MYTH Inc Forbidden Land

Forbidden Land Corridor of Storms

Corridor of Storms The Peytabee Omnibus

The Peytabee Omnibus Beyond the Sea of Ice

Beyond the Sea of Ice The Time Of The Transferance

The Time Of The Transferance EarthBlood

EarthBlood The Lexal Affair

The Lexal Affair The Web

The Web Slave Ship

Slave Ship Eternity Row

Eternity Row Planet Pirates Omnibus

Planet Pirates Omnibus Aztec

Aztec The Awakening

The Awakening Aztec Blood

Aztec Blood The Mystery of Ireta Omnibus

The Mystery of Ireta Omnibus Aztec Autumn

Aztec Autumn The Savage Horde

The Savage Horde Anti - Man

Anti - Man Deep Trek

Deep Trek Starfall

Starfall The Paths Of The Perambulator

The Paths Of The Perambulator Fool's Fate

Fool's Fate Jinian Stareye

Jinian Stareye Endurance

Endurance Spellsinger

Spellsinger Hybrids

Hybrids Beyond Varallan

Beyond Varallan Doona Trilogy Omnibus

Doona Trilogy Omnibus In th Balance

In th Balance Planerbound

Planerbound The Nightmare begins

The Nightmare begins Humans

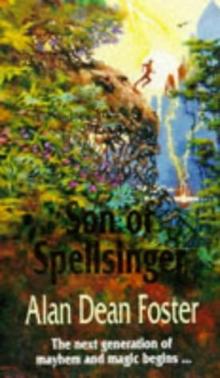

Humans Son Of Spellsinger

Son Of Spellsinger